|

Finally, Gentle Readers, a weekend that felt like spring! But I confess I haven't been complaining much because we were away for a couple of weeks, and the lingering cold weather gave me some extra time to do cleanup and other early season chores, like pruning. Which brings me to the topic of this post: pollarding. For those of you not familiar with the term, it's a traditional tree pruning technique that involves the regular removal of new growth back to a stump or candelabra-like structure for practical or aesthetic purposes. As Americans we tend towards an aversion to any form of tree pruning, except for fruit trees. Our dominant aesthetic is naturalism, and we decry techniques like pollarding as butchery and desecration of the normal growth of the tree. The Europeans haven't such a limited view of the matter. Our trip, to Germany and Central Europe, provided plentiful examples of the technique that were especially evident so early in the season, before the trees began to leaf out. I was struggling to identify most of them from the bark alone, but many types of broadleaf trees are treated thus, particularly Lindens, Planes, Hazels, Hornbeams, Horse Chestnuts, Oaks and Willows. Obsessed as I was with taking pictures of pruned and pollarded trees, I want to emphasize that the vast majority of trees we saw in parks and gardens were allowed to grow in their natural form. But where they deem it appropriate, European gardeners are never shy to take up the pruning shears. Shaping, shearing, pollarding, pleaching and of course topiary are all highly developed horticultural skills there that are used to effectively contrast and compliment the natural growth of other plants and to provide living architectural form. Pollarding is an ancient technique that's mentioned in Roman writing and has been widely practiced in Europe since at least the Middle Ages. It had, originally, very practical purposes: to provide fodder for livestock, easily harvestable fuel for fires, and long, supple stems for basketry and wickerwork. The term comes from the word "poll", an old term for the top of the head, therefore "topping" the tree at the head. Interestingly, studies have shown that this unnatural treatment maintains trees in a nearly perpetual juvenile state, so they live much longer than their unpruned counterparts. There are numerous examples of pollarding in Europe that have been maintained continuously for hundreds of years. Nowadays pollarding is done primarily for aesthetic purposes, and to maintain trees at a size that's more manageable and consistent in relation to architectural features, along streets or in courtyards and other urban settings. Pollarding and other traditional management techniques, like coppicing, are also enjoying a revival in agriculture among permaculturists. A stand of pollarded trees allows much more light to reach the ground, so creating pasturage for animals below and harvestable material above. Maybe it's an acquired taste, but I really like the sculptural quality of the knobbly heads, shaped by many years of pruning, and soon to be covered in fresh leafy growth. If you want to try your hand at pollarding, you must start with a young tree so an open and balanced branch structure can be developed over time. The pruning can be done any time after the leaves drop in fall but before the trees break dormancy in the spring, so it's a pleasant chore on a warmish late winter day when you're just dying to do something outdoors. Once you develop a pollard you have to maintain it by pruning back to the developing knob every year. Keep in mind that pollarding is an intentional technique, not at all the same as topping, which is what our road crews do to already mature trees around utility wires. That really is mutilation. I've been pollarding a line of Coral Bark Willows on my property for several years now, gradually developing a pleasing branch structure with bushy heads of summer growth at just the right height to screen my unsightly neighbor. Our garden is not at all grand, so the willows are at the back of a shrub border and planted in a staggered line, and the effect is more farmstead than formal. It solves a screening problem for me, and I enjoy the brightly colored shoots all winter, until I do the pruning in very early spring. Although it's definitely not for everyone, if you have an appropriate setting don't hesitate to use pollarding as a striking horticultural feature or a practical problem-solver. With a long and respectable history, it's a technique that more Americans should look at with an open mind! It wasn't all bare trees in Europe... spring was already happening there, as evidenced by these Hepaticas blooming in the woods near Munich.

1 Comment

My neighbors must have thought me completely insane this weekend, seeing me out in a parka and heavy gloves, cutting down grasses and perennial stalks at my place which is still half under the snow (one consolation: dragging a heavy tarp laden with soggy plant debris is much easier over snow than over lawn!) I just couldn't resist a sunny day; even though the temps were barely above freezing and the wind was raw, it was good to be moving again and at least making a beginning at spring cleanup. In spite of the mad labor involved, I love spring cleanup most of all for the surprises it holds of emerging and forgotten favorites... the day's efforts revealed budding Hellebores and unfolding species Tulip foliage, plus the still-pointed shoots of Fritillarias, Trilliums, Alliums, Crocus, Phlox and Peonies. And remarkably, the apparently cold-proof leaves of Forget-Me-Nots that have remained fresh and green under the snow cover. Most perennials haven't yet revealed themselves, but one that has, and a true herald of spring, is the Cowslip Primrose, Primula veris. The leaves push up through still frosty ground, green as a bean and slightly velvety, crinkled and pleated and ready to unfurl in the first really warm week of the year. As a beginning gardener I was a bit intimidated by Primulas, and many of them are indeed collector's plants for the knowledgeable enthusiast, but there are three species that I can recommend as easy, reliable and lovely. Cowslips were the first I tried and succeeded with, and are still my favorites. All they require is average soil that never completely bakes in the summer, and protection from the hottest afternoon sun. Full sun in early spring is ideal, though, so siting them under deciduous trees is a good plan as long as the soil is reasonably moist. The default color is a fresh shade of lemon yellow, but they also sport into bronzy orange and even rich red. I'm sure there must be a white version somewhere (probably England) but I've never seen it for sale here. I like to separate the colors and make big patches that carpet the ground beneath my River Birches (the yellow) or complement the blue flowers of Woodland Phlox (the bronze). I find the red one a bit more difficult to place, but it's certainly vibrant and eye-catching. Being pasture weeds in their native Europe, they're easy as pie and can be divided any time from just after bloom until around Labor Day. Another little beauty, just as easy to grow, is Primula sieboldii, a native of Siberia, Korea and Japan that comes in shades of white, pink and magenta, many often exhibiting dual coloration with the backs of the petals different from the fronts. The flowers look a bit like snowflakes with varying degrees of fringing and dissection, making for a very charming lacy effect that belies their ease of cultivation. The plants are stoloniferous and will make large patches in time (as seen above at Berkshire Botanical Garden)... all they ask is consistently moist soil and shade in the summer months. The foliage may even disappear below ground after June, but will return the next spring, when you've forgotten all about it. They make great companions for other diminutive spring treasures like Epimediums, Trilliums, Asarums, Anemonellas and Dodecatheons. The third easy Primrose is another Asian native that will make itself right at home here if you have a very moist (even boggy) site, ideally along a small stream or at the edge of a shady pool. This is the Japanese or Candleabra Primrose, Primula japonica. The basal rosettes of bright, lettuce-green leaves are topped by tiered clusters of dainty flowers in every shade from white though all tints of pink to dark rose, and some even come in an unusual deep coral tone. In rich soil the flowering stems can reach eighteen inches in height, with several tiers of bloom that open in succession, making for a spectacular display when planted in quantity. Where happy they will seed themselves freely, so it's hard to maintain separate colors without thinning them as they bloom, but if you have a particularly nice shade you can always divide it after flowering, keep the divisions watered for a couple of weeks, and you'll increase your stock three- or more-fold every year. Rich, consistently moist soil is key to growing these beauties, but if you have those conditions they will thrive with very little care. There are, of course, dozens of other Primroses that you can try, many of them quite choice and rare, if you become enamored of the genus Primula. But for general purpose gardening, I heartily recommend these three beautiful, easy and rewarding Primroses. Give them a try, and reap the rewards of early spring bloom for many years to come! Why I'm Splitting with Six Popular Plants We need to talk. You're a beautiful, desirable plant, one any gardener would be lucky to grow. But something's changed, and I just don't feel the same way anymore. The last thing I want to do is hurt your feelings, but I really feel the need to be totally honest here... I'm sorry, but you've been seen around town WAY too much lately. I'm old enough to remember when Russian Sage, Perovskia atriplicifolia, was a hot new plant that everyone wanted to try. And we did. Tough, easy, and with a go-with-everything blue and silver color scheme, it became one of the most popular perennials in the repertoire. And therein lies the problem. Do I really want to give precious garden space to a plant that's now seen in every suburban tract house foundation planting and Burger King drive-through? I'm afraid I don't. Foolproof though Perovskia is, I'll get my blue/purple spikes elsewhere now, from newer alternatives like Salvia pratensis 'Ballet Sky Dance' (right below) or even Agastache 'Blue Fortune' (left below, covered in butterflies), almost as well known as Perovskia but with the added bonus of being a better pollinator plant and having superior winter interest. You're gorgeous, but you're so needy and high maintenance it's killing me. Because I grew up in the deep south, where they absolutely will not thrive, big double-flowered Peonies were one of the first plants I wanted to grow when I started gardening in the north. Their lavish blooms, delicious fragrance, and romantic names (Lady Alexandra Duff, Sarah Bernhardt, Duchesse de Nemours, etc.) were irresistible. But after a few years their allure barely seemed to offset the brief flowering period, the susceptibility of the foliage to mildew and viruses, and the near impossibility of staking them attractively and inconspicuously. Full disclosure: I still grow some of them, but they've been banished to a cutting area in the back of the kitchen garden where I can harvest the blooms for vases but forget about the plants for the rest of the season. In my perennial beds I now grow only the shade tolerant Japanese Woodland Peony, Paeonia japonica (left below) and 'Krinkled White' (right below), a reliably sturdy single herbaceous type. Neither needs staking or much maintenance beyond an annual cut-down at year's end. You're just too much of a flake... and your tacky outfits are way over the top. Echinaceas are one of the plant groups (like Hostas, Heucheras, Daylilies and a few others) that the plant breeders have gone wacky over, churning out endless new varieties each season, novelty upon novelty. What was once a reliable American wildflower has now become a collector's plant, and I've had enough. Although new colors were welcome at first, now the pretty, original shuttlecock form has been splayed open, doubled, pom-pomed and otherwise deformed, distorted and debased until it's unrecognizable. Worse yet, none of the newer varieties I've tried have proven to be particularly vigorous or long-lived. (Echinaceas aren't naturally perennials that have a long life span... in nature the crowns live only two or three years, and repopulate mainly through seed dispersal) Call me cranky, but I'm back to planting only the straight species, Echinacea purpurea (below), and its closely related variations like the shorter 'Kim's Knee High' or the white flowered version, 'White Swan'. Frankly, Annie, you've put on too much weight. Yet another case of overdevelopment, and of bigger not being necessarily better. Hydrangea arborescens 'Annabelle' has enormous mopheads that often can't be supported by the branch structure, so you frequently see her bent over after a rain, dragging her blossoms in the mud. Not pretty. And don't even get me started on the even larger and more grotesque 'Incrediball'. Awful name, awful plant. Instead, opt for the Hydrangea arborescens varieties with lacecap heads like 'Haas Halo' (top below) and 'White Dome' (bottom below). Same tough and hardy American native genes, but with an altogether lovelier flower form than 'Annabelle' that remains self-supporting in all weathers, and even looks fetching when snow covers the dried flower heads. Mother tried to warn me about tramps like you. Rampantly promiscuous, Nicotianas (the Flowering Tobaccos) interbreed madly and throw off millions of dust-like seeds, resulting in carpets of seedlings whose large leaves smother nearby plants, and seldom turn out to be the color you wanted. After several years of trying to manage them by thinning and deadheading, I've decided that ruthless extermination is the only solution. Now I just hoe them out like common weeds, and I find that I still have a satisfying garden without them. Nothing else has quite the same flower effect, but for a scattering of clean white in the same area, I'm dividing and increasing my clumps of the Japanese Aster, Kalimeris integrifolia 'Daisy Mae' (below), a reliable and well-mannered clumping perennial with a long season of bloom and clouds of crisp, dainty flowers in May and June. Not the same as a Nicotiana, of course, but far easier to manage. I'm sorry Karl, but you're just too... uptight. I know, I know... Calamagrostis 'Karl Foerster' is a modern classic. It's one of Piet Oudolf's favorite grasses. It's reliable, hardy and readily available. And it's got a really long season of interest that peaks in a beautiful golden wheat-like inflorescence. But somehow, I just find it so... rigid. And though I plant and love many tall, upright and vertical perennials like Veronicastrum, Vernonia, Liatris and Coreopsis tripteris, I still can't seem to warm up to Karl F. When I need a tall grass with a handsome flowering, I prefer the more graceful Calamagrostis brachytricha (top below at Hudson Bush Farm) or Frost Grass, Spodiopogon siberica (bottom below). Both have height, presence, late interest and a more relaxed form that I think blends with other plants more effectively. Of course, the whims of a gardener being what they are I'm not guaranteeing I won't grow any of the above ever again. In the meantime, I think we both need to see other people. But don't worry, we can still be friends, can't we? Happy Valentine's Day. "Beautiful young people are accidents of nature, but beautiful old people are works of art." A quote usually attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt, although her grandson and biographer claims she never said it. Whoever did, though, was correct... to project beauty, dignity and refinement as the years pile on requires effort and yes, artistry. I think of my own Great Aunt Ellanor, one of the many talented gardeners in my family, gone for many years now but a formidable presence in my youth. Born in the 19th century, she still carried a hint of the northern English brogue inherited from her hard-working immigrant parents, who had somehow ended up settling down in a small town on the Gulf Coast of Texas. Early photos of Aunt Ellanor show her following the fashions of the day, as any young person would, but by the time I came along she'd pared down her taste to a dignified minimum, and I can only remember her wearing black or navy blue dresses that set off her beautiful snow white hair, always pinned up in a twist at the back of her head. And though her face was a roadmap of creases, her clear blue eyes never missed anything, and her wit remained sharp until her last days. We should all age so well, and a huge movement is underway now in the world of horticulture to create gardens that age well also. Gardeners everywhere are learning to look at plantings more holistically, and accept cycles of growth, decline and renewal as each having a beauty of its own. At this time of year, when flowers are long gone, it's tempting to retreat indoors until the first spring bulbs emerge, but if we only open our eyes a bit there's still much to be appreciated in the structure of branches, seed heads, grasses and so many more plant forms that reveal themselves once the garden's palette is reduced to near monochrome. And as Piet Oudolf has remarked, "Brown is also a color." Striving to extend my garden's seasonal interest, I plant more grasses, fruiting shrubs and structural perennials every year. Morning light enhances the sculptural quality of many grasses, like this Giant Sacaton (Sporobolus wrightii 'Windbreaker'), here backed up by the golden fall coloring of Amsonia hubrichtii. Panicum virgatum 'Northwind' glows in the low winter light, and is sturdy enough to stand upright through most of our snowstorms. Pairing tall grasses with evergreens, like this native Bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica) provides food, cover and wind protection for birds and other small wildlife. Even the smaller grasses, such as this Hakonechloa macra 'All Gold', take on interesting colors after a hard frost, turning from its usual chartreuse to a beautiful silvery green. Leaving some perennials standing and allowing them to develop their seed heads provides food for many birds when snow covers the ground. These porcupine heads of Echinacea purpurea are a favorite of Goldfinches. Many perennials that bloom after midsummer develop interesting and decorative seed heads. Left to right: New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveborecensis), Agastache 'Blue Fortune', and Ligularia japonica. The fruit on my Viburnum dilatatum 'Cardinal Candy' must go through several more cycles of freezing and thawing before they sweeten enough to be palatable to the birds... then, in a matter of hours, they will be stripped and gone. A few years ago I planted a row of seven Coral Bark Willows (Salix alba 'Britzensis') at the back of a shrub border to screen our neighbor's house from view. An annual pollarding in early spring keeps them dense and promotes colorful new shoots each season, at their brightest in late winter. We tend to think of fall color only on trees, but many perennials put on quite a show before they drop their foliage, like this Epimedium 'Freckles'. I plant the non-hardy Pennisetum 'Vertigo' every year to enjoy its bold, deep purple foliage all summer. After the first hard freeze, it collapses into a spooky frozen waterfall that I find equally appealing, and provides good shelter from winter winds for small birds. A couple of weeks ago I was lucky to be included in an outing to a garden I've long wanted to visit: James Golden's 'Federal Twist', in central New Jersy. The visit was organized by the wonderful Peter Bevacqua and included fellow garden pros Betty Grindrod, Heather Grimes and Kurt Parde. Prior to our arrival, James had expressed concern that there would be little left of interest so late in the season, but we were far from disappointed. The two acre garden is intensely planted, with no lawn and meandering paths that lead through the dense, layered plantings, some so tall that they astonish in an Alice-in-Wonderland way. Grasses are the leitmotif here, especially Miscanthus species and cultivars, but also Panicums, Pennisetums and Schizachyriums. Rudbeckia maxima and other giant forbs blend and weave among the grasses on the wet clay site, while smaller plants carpet the ground underneath. Heather collects seeds from a white Baptisia. This is the time of year to gather pods, cones and seedheads for wreaths and winter arrangements. The stark black stems of a frosted Eupatorium stand in contrast to the arching grasses, still holding onto a bit of summer green. At the bottom of the garden, a black pool reflects the November sky. This is an enchanting place, a testament to how beautiful a garden can be even so late in the year, and well worth a visit at any season. To learn more about the garden and be apprised of upcoming open days, subscribe to James's excellent blog, "The View from Federal Twist" at federaltwist.com. Restraint, discernment, an appreciation for subtleties... all marks of maturity as a person and as a gardener. I value these qualities more every year, and strive for them in my plantings. And as another birthday approaches next month, I hope for them in myself. We've had such a beautiful stretch of weather lately, still summery but foreshadowing fall, and I feel renewed and refreshed enough to do some ambitious gardening again. This is a great time for planting perennials and flowering shrubs, the warm days and cooler nights perfect to encourage plants to root in and establish before the real fall weather arrives. And there are many plants that save their biggest show for this time of year: Sedums, Asters, most of the ornamental grasses and many others. One of the most spectacular late-bloomers is Hydrangea paniculata 'Grandiflora', the "Peegee" Hydrangea (pictured above) an old-fashioned shrub that's often seen around local farmhouses. Its big pointed clusters of white flowers age to pink as the season progresses, and are often cut for dried flower arrangements. It's a classic, but there are lots more varieties that have been introduced since the "Peegee" came on the market just after the Civil War. Hydrangeas are a large and varied group, native mainly to Eastern Asia and North America, and the many kinds seem to cause a lot of confusion among gardeners... in fact, they occasion some of the most frequently asked questions, such as "why won't my Hydrangea bloom?" and "what kind of Hydrangea do I have?" In this post I'll attempt to clarify some of the confusion and show you just a little of the great variety in this really beautiful genus, a favorite of mine. When explaining the differences in Hydrangeas, I like to break them down into four main groups for simplicity's sake: The four main categories of Hydrangea for our Zone 5 area are (clockwise from upper left) Oakleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia), Smooth Hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens), Panicle Hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata), and Mophead Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla). Let's start with the most distinctive and least confusing: the American native Oakleaf Hydrangea, Hydrangea quercifolia. This beauty is found in woodlands all through the southeastern states, but will grow well in our area although a really harsh winter will sometimes knock it back to the snowline. However, it quickly regrows from undamaged portions and will even begin to sucker at the root, forming a well-mannered colony in time. What makes this Hydrangea so distinctive is the beautifully shaped foliage, recognizable enough for even a child to identify, that turns gorgeous shades of gold, orange, scarlet and wine red in fall. The bark is interestingly shaggy also, and the fuzzy buds are cute. It flowers in mid- to late summer, the long panicles turning pinkish-red in some cultivars (like 'Ruby Slippers') or just a pleasant shade of blush or tan in the straight species. One of the very best native shrubs, with only one caveat: the deer relish the fuzzy buds in winter, so grow in a protected area or net it until it grows above the browse line, usually four or five feet. Oakleaf Hydrangeas need very little pruning, just a shaping from time to time, removal of dead branches and cleaning up last season's tattered flowers in late winter or early spring. Next comes another tough American native, the Smooth Hydrangea, Hydrangea arborescens. Most people are familiar with this in one of its cultivar forms, the large-flowered 'Annabelle' (left above), but there are several lovely varieties in commerce as well as the straight species. 'Incrediball' (awful name) has flowers even larger than 'Annabelle' and 'Invincibelle Spirit' (right above) is a pretty soft pink version. These types will grow and flower well in full sun, but I think they're best when given high dappled shade from tall trees or only morning sun, as hot afternoon sun tends to make them wilt and look a bit tired. For a more naturalistic look, there are lacecap versions too, like 'Haas Halo' (top above) and 'White Dome' (bottom above). I love these for their cool summer flowers and especially for their ability to hold snowfall in the winter. All the arborescens types can be cut almost to the ground in the spring if you want the largest flowers (but fewer of them), or pruned back by one third for smaller but more numerous flowers. They bloom on the current year's growth. Equally tough and hardy, though not native, are all the Panicle Hydrangeas, Hydrangea paniculata cultivars, including the well-known "Peegee" that I mentioned at the beginning of this post. These are some of the most reliable shrubs for our area, and come in many beautiful varieties... some of the best are 'Limelight', which opens a cool greenish-white and ages to pink, 'Phantom' (above) boasting enormous flower clusters, 'Quickfire' and 'Pink Diamond', with open panicles that color up fast to deep rose pink, 'Unique', another one with large lacy flowers, the late-blooming 'Tardiva' and many others. All these are large shrubs, eventually 8-12 feet tall, but there are dwarf varieties available too, like 'Little Lamb' and 'Bobo', to fit into a smaller planting scheme. Very often nursery customers will ask for a "Tree Hydrangea", but really, there's no such thing. What they're looking for is a paniculata type that's been trained into what's properly called a standard, a horticultural form that looks like a small tree, with a rounded head on top of a slender "trunk". Best used in very formal settings, these are elegant when well placed but can sometimes topple and break in winter storms, in which case they will regrow from the root in the plant's natural form, a multi-stemmed shrub. All the Hydrangea paniculata varieties flower best in full sun, and bloom on the current season's growth, so they should be pruned in early spring before they leaf out, and can be pruned hard (down to half the size) or moderately (removing 1/3 the size of the shrub). Panicle Hydrangeas can make dramatic landscape statements. This is 'Limelight'. Last of the four groups is the one that seems to cause the most consternation, at least in our Zone 5 climate: the Mophead Hydrangea, Hydrangea macrophylla. These are the gorgeous blue Hydrangeas that are such a feature of Nantucket, Cape Cod and Long Island, and southward all the way to the Gulf Coast. They are also hugely popular in Europe, where they are known as Hortensias, and were hybridized in hundreds of beautiful varieties in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The sad truth is that these romantic beauties are not well suited to our winter climate, because they set their flower buds a year ahead and must winter them over to bloom well. The plants will survive, but not the flower buds, so flowering is typically sparse, often only below the snow line, but they're sold in every big box nursery and grocery store, leading to much confusion about their hardiness. Recently, some varieties have been developed that flower on the current year's growth, like 'Endless Summer' (blue, above), 'Blushing Bride' (white flushed pale pink), 'Twist-n-Shout' (pink or blue lacecap, left below), and 'Diva' (very large pink lacecap, right below). The jury's still out on these in our area, as they've only been on the market a few years, but some local gardeners report success, and if you must have a blue Hydrangea these are the only ones to consider here in the Hudson Valley. There's also quite a bit of mythology about changing the color of these Hydrangeas from pink to blue or vice versa... the pH of the soil and the presence or absence of aluminum in the soil is determinative, but adding pennies, nails, aluminum foil or coffee grounds will not do the trick! Mopheads have glossy, smooth leaves and appreciate shade from the hottest sun and reliable moisture. Pruning should be done in spring, but sparingly and only to remove spent flowers and tips that have winter-killed. and

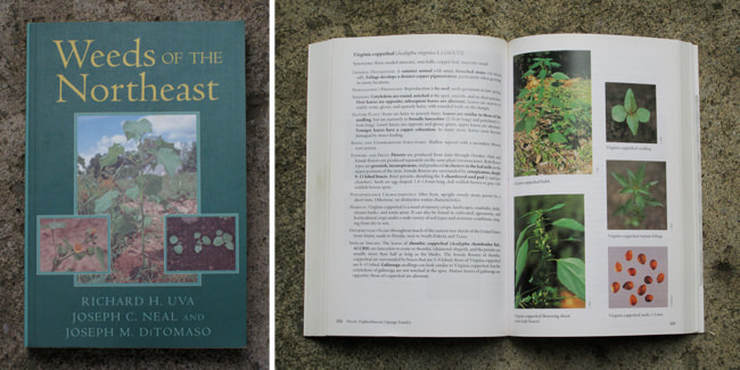

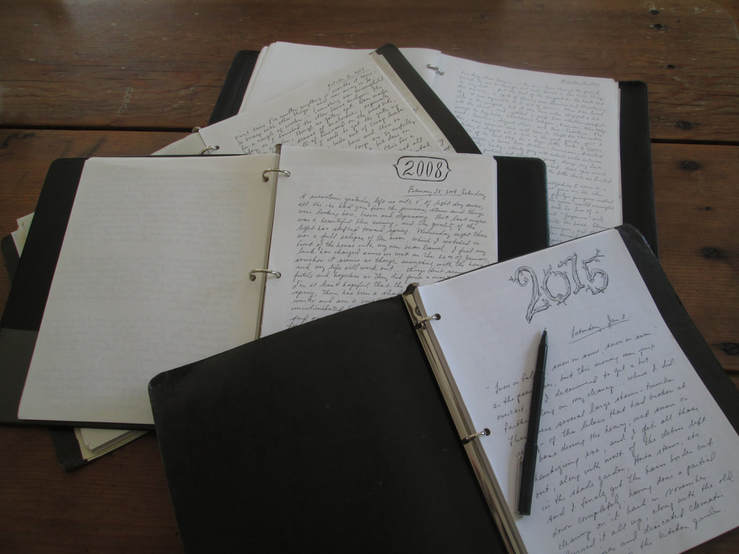

There's one more type of Hydrangea I want to mention, because it's such a beautiful plant, well suited to our area and can't be confused with the four groups above... that is, the Climbing Hydrangea, Hydrangea petiolaris (shown above at the much beloved local garden of Hudson Bush Farm). This requires patience and a very sturdy pergola, fence or masonry wall for support, because once it's established and really starts growing it can become quite a lovely monster. Although slow to settle in, it isn't too picky about soil and tolerates quite a bit of sun. It can be used to perfection spilling over an old stone wall. That's my little tutorial, and I hope it's clarified some questions for you. Hydrangeas are so varied that some confusion is inevitable, but don't let that stop you from growing and experimenting with these handsome plants, so many of which will do well here in our region. A competent nursery will always be happy to guide you in your selection and help you find the variety that suits your property best, whether it's a farmhouse, townhouse, mansion or suburban ranch! Yes, Gentle Readers, I'm back to writing after a hectic opening season and several off-site sales that are always fun but a lot of work hauling plants, setting up and bringing everything that didn't sell back to the nursery. But it's great to get out in the community for these events to see our regular customers and connect with new ones. And of course at Pondside we're always running flat out between Mothers' Day and Memorial Day. But now that summer's really here we're settling into a still busy but less frantic schedule, and I thought it might be a good time to take a look at one of the biggest maintenance issues for all gardeners: WEEDS! I confess to being somewhat fascinated by weeds, admiring their adaptability and persistence and, often, their undeniable beauty. But when they threaten to overwhelm my other precious plants, it's time to spring into action and get them under control. Here I'll be sharing some strategies for staying ahead of them and steadily reducing their numbers in your garden. First, the bad news: there's no way around it, no magic bullet, no secret plan to eliminate weeds without work and persistence. It's just a part of gardening... a BIG part... and new gardeners in particular are often overwhelmed by the sheer labor involved, especially in newly planted areas. But the good news is that it gets better over time, becomes more manageable as your garden matures and can even become an enjoyable task if you stay at it and avoid procrastination. There are a couple of weapons in my arsenal that I just couldn't garden without: a weeding fork and a weeding hoe. The weeding fork is a hand tool with sturdy prongs to penetrate the soil, leveraging the weed and its roots out of the ground with a quick and efficient action. By using the fork with one hand and grabbing the weed and shaking off the dirt with the other, you can cover a lot of ground in short order, and the loosened soil that results is less conducive to weeds sprouting than firmer ground. The fork is my favorite weeding tool, and we sell several versions at the nursery. Some gardeners prefer the Japanese Hori-Hori knife or a pronged cultivator, both of which we also sell, and the principle is the same. Any of these hand tools are best for removing maturing weeds, and weeds growing closely among other plants. For larger areas, like paths in a vegetable garden, and tiny weed seedlings too small to pull individually, a weeding hoe is ideal. Hoeing (the horticultural kind) is something of a lost art, but I remember my grandmother keeping her beds and edgings weed-free with just a small hoe that had been sharpened so many times that the blade was as narrow as a kitchen knife. I have a narrow-bladed hoe also that works wonders, slicing just below the soil surface to separate the tops of the weeds from their roots. Work forward, taking out the weeds nearest your feet before you advance, and do it on a hot day so the sliced weeds will dry to a crisp that's virtually invisible. It takes a bit of practice to get just the right angle to slice the weeds without digging up a lot of soil, but once you've mastered the technique it requires little effort and provides a nice upper body workout. If you're dealing with very deep, tap-rooted weeds like Dock or Dandelion (a frightening example shown in the photo at the beginning of this post) a Dandelion fork is a useful tool. These have a slender blade with a sharp, notched end that allows you to penetrate deep into the soil and loosen the taproot for full extraction. Sort of like dental work. The Hori-Hori works well this way also. Which brings up the legitimate issue of how do you know if it's a Dock or a Dandelion or whatever, especially if you're a novice gardener? Well, here's where my garden geekiness gets totally unrestrained, because I'm going to suggest that you buy a book on weeds. I confess to having several, but the best for our region and the only one I really recommend is Weeds of the Northeast by Uva, Neal & DiTomaso, from Comstock Publishing. You can get a gently used copy for about twenty bucks (and support an independent bookseller) by ordering from Alibris.com. What I love about this book is that it has multiple photos of every weed, in different stages of growth from seedling to flowering, and has enough text to provide accurate identification without becoming overly technical. It's kind of fun to put a name to all those things you've been pulling out for years, but more importantly you can learn a lot about the life cycles of the plants which will help you strategize about how to control them. For instance, take the pesky Garlic Mustard, a common biennial weed hereabouts. Biennials make a compact rosette of leaves the first year, but don't flower and set seed until the second, so if you can't manage getting all the plants out, concentrate on the flowering ones. The white flowers are easily spotted and you can attack them and worry about next year's plants later, if need be. Timing is really critical with weeding. There's an old farmer's saying: "One year's seeding is seven year's weeding", which means that if you let a weed go to seed, you'll be dealing with its progeny for years to come. And I mean years... there are weeds whose seed can remain viable in the soil for forty years. That's not a typo, I don't mean four years, I mean FORTY. So try, really try, to get those weeds out before they set and ripen their seed, which can happen remarkably fast after they flower. Another strategy for killing weeds and/or lawn grass in an area to be turned into a bed is smothering. I use flattened cardboard boxes to cover the area, hose them down until saturated, and cover with a layer of mulch or shredded leaves. If you do it in the fall, most everything will be smothered by the spring and the cardboard will have deteriorated to the point that you can dig right through it to plant. An even more thorough technique is solarization. It takes longer (up to six months) and is less attractive in process because it requires covering the area in clear plastic sheeting to basically cook all the weeds, weed seeds and pathogens underneath. But it can be very effective. Lots of detailed information on the internet if you want to learn more. I do everything possible not to use herbicides because they're terrible for the environment and you risk accidentally destroying desirable plants nearby. However, if you're faced with a really major infestation of the worst kind of weeds, say Poison Ivy or Canada Thistle, the nuclear option may be your only chance to get control over the situation. Mix your own concentrate at two-thirds the recommended strength and spray on a hot, still day. Glyphosate is the safest and least lingering product. Again, know your weeds and try other strategies first, only using herbicide as a last resort. When all is said and done, no matter what your method, persistence is the real secret to keeping ahead of those weeds. Instead of putting it off until you can have a "weeding day", make it part of your daily routine. Better to spend fifteen or twenty minutes a day, every day, than to wait until you can devote a large block of time to the task. If you have time in the morning, take your second cup of coffee out with you. Or if you tend to garden in the evening, a glass of wine is a nice compensation for a half-hour spent pulling Crabgrass. With all the rain we've had this season, even the most diligent gardeners are having a hard time keeping up, but don't be discouraged. With patience and determination, you will reduce your weed population over time, and because it's one of those jobs that provides instant gratification, you may even learn to enjoy weeding as much as I do (but I'm weird). January's been awfully grey and gloomy, with some warmish periods that seem almost like March, but we're once again under snow cover and back to somewhat normal winter temps, keeping plants properly dormant and protected from frigid wind. For gardeners this is the time for rest, planning and evaluation. Much can be accomplished now that the holidays are over and the rush of spring chores hasn't started, so there's no reason to succumb to depression and despair! Here are some tips for getting through, and getting things done... I love looking at plants, and over the years I've developed an enhanced appreciation for those that look good in winter, when we really value a little dose of color in the midst of the white, grey and brown landscape. Broad-leafed evergreens are few and far between for our climate, but one that I've grown for years is a very hardy cultivar of the Swamp Magnolia, Magnolia virginiana 'Moonglow'. It does lose some leaves in the winter months, and in colder winters will bronze out completely by spring, but so far this year it's withstanding the weather and providing a nice spot of greenery along my little stream. It's really a star during the warm months, offering an upright outline and small but exquisite lemon-scented flowers in July. I love Viburnums too, and encourage gardening friends to try more of the many great species and varieties of these beautiful and useful shrubs. One of my favorites is 'Wentworth', a selection of the native Cranberry Viburnum, Viburnum trilobum. It's a tall shrub that gradually suckers into a nice, non-invasive clump, wonderful for naturalized areas but refined enough for a more formal planting too. The beautiful clusters of fruit are eventually eaten by the birds, but must not be palatable until they've frozen and thawed several times, because mine are always pretty persistent through the winter. Beeches and Hornbeams are trees known for holding their leaves through the winter, which makes them valuable for hedging, but many Oaks have persistent foliage as well. My Scarlet Oak, Quercus coccinea, still pleases me with the glowing tobacco brown leaves that followed its bright red fall color, and hang on until the new buds break in spring. Most perennials retreat underground for their winter dormancy but there are a few exceptions, even here in Zone 5. Yuccas have a bad rap with many gardeners, probably because they're often seen isolated in the middle of a lawn surrounded with white gravel, but I love their strong form and persistent foliage. Use them singly, or better yet in bold groups, to provide a gutsy linear texture among fussier perennials. Yucca filamentosa comes in basic green or in several nice variegated forms like 'Bright Edge' (above) or the even showier 'Color Guard', which is the reverse variegation with yellow centered, green edged blades. Another perennial that seems dauntless in cold weather is the Bear's Foot Hellebore, Helleborus foetidus. It must have some kind of built-in antifreeze because when the temperature dips below 25 or so it turns almost black a shrivels, and I'm sure it won't recover, but when there's a warm spell it recovers its color and form completely. The flower buds have been formed since fall but they seem to be soldiering through unharmed, waiting to blossom in April. Taller than most other Hellebores, it thrives in woodland soil, can tolerate dry shade, and though individual plants aren't extremely long-lived, will reseed itself when happy. Many ornamental grasses took a beating from the heavy snowfall we had back in December, but Panicum virgatum 'Northwind' lived up to its reputation for being one of the most upright native grasses. It manages to spring back even after being coated with ice. These young plants of 'Northwind' (left above) were just planted in July, and they've already proven very valuable for winter interest. Completely different in effect is Bouteloua gracilis 'Blonde Ambition' (right above), with wiry stems so delicate that the snow can't cling and break them down. There's plenty of twiginess in the winter garden, some of which is very attractive in form and color. Just about every gardener knows the red stemmed Dogwoods, and Cornus sericea 'Cardinal' (left above) is a great cultivar, taller than many, which makes it useful as a screening shrub in summer. There are also variegated, golden-leaved, and yellow stemmed Dogwoods that can add even more variety to a planting. Many Willows develop vibrant winter stem color too, like Salix alba 'Flame' (right above), a large shrub/tree with bright golden orange to red bark that looks gorgeous against the snow. It can be stooled down to 1 ft annually in early spring if you want a bushy hedge or screen, or allowed to develop into a tree. I'm a big fan of the native Hydrangea arborescens, especially the lacecap versions that catch and hold the snow so beautifully. I have a group of 'White Dome' (above left), an older variety that's inexplicably hard to come by now, but I've also recently planted several 'Haas' Halo' with even larger and more voluptuous flower clusters. Magnolias (above right) aren't colorful in winter, but their elegant branching habit is very pleasing and the fattening buds look promising silhouetted against the grey January sky. I tend to think of container plantings as a summer feature, but with a little imagination they can be designed to be quite decorative through the colder months as well. Here, little dwarf evergreens make an interesting group in a frost-resistant trough, handling ice and snow as well as the full-sized versions. You could also make a nice display of grouped containers planted up with easy and hardy rock garden perennials like Sedums, Sempervivums, Orostachys and the like. Daily walkabouts are not only good exercise but helpful to see your property in a different light, stripped down to its essential layout. Devoid of flowers and most foliage, your garden will reveal its design strengths and weaknesses, suggesting where edits are needed and additions required. You can even lay out new planting areas when snow is on the ground, as I've done in the photo above. I find it easier to see the outline I want on this white canvas, and 2 ft. rebar stakes can be driven into frozen ground with a hammer after roughing out the line by walking it in boots. The stakes will still be in place come spring when I'm ready to cut the edge. Reading is of course a prime winter activity for most of us plant-obsessed people, but why not try some informal writing as well? As a young gardener trying to learn the sequence of flowering, I started keeping a weekly list of what was blooming. This was around 1980, when I had my first real garden. Over the years that evolved into a full-fledged (albeit sporadic) garden journal that has given me a lot of pleasure... and preserved much useful information. Often I'll refer to the last couple of years' entries while I'm planning the next season's work or trying to remember the name of something recently planted. But sometimes, maybe once a year, I'll look back at some of my oldest entries. It's amazing how much I've forgotten that I once grew, and how far I've progressed as a gardener. I read the names of mail-order nurseries now long out of business (then my only source of unusual plants) and the occasional notations of life events: the birth of a friend's first child, the death of a pet. But mostly it's weather, what's blooming, what's been bought and planted and where, what's turned out to be the color advertised (or not) and what's established and thrived, and of course, what hasn't. Some of the entries really make me laugh now... here, a rant from April 1995: "Mail-order nurseries are the worst... planted today a bone-dry stick that cost $12 (plus shipping!) from Burpee... if it grows into the yellow Trumpet Vine it's sold as, it will be a miracle, and take years. If Trumpet Vines weren't so weedy I'd have no hope at all. This precious treasure arrived in a padded envelope, tied to a bamboo stake, without a bit of moss or soil, the fleshy root itself broken in two places." More often, though, I'm writing about something delightful... the first Daffodil, or a surprisingly happy plant association, or some perennial that returned three-fold from the year before. Looking back, I can believe that most everything was worth recording... writing things by hand has been proven to solidify things in your memory... and because the gradual accumulation of that experience has made me a better gardener. The beginning of the year is a great time to take up your pen (especially you young gardeners) and start to record what you think you'll remember (but won't), what are your successes and your failures, your favorites, surprises, disappointments, goals, frustrations and dreams. Don't make it a chore, just an occasional pleasure... sometimes in the busiest part of the year I go several weeks without making an entry, but I always return and catch up. Trust me, ten or twenty years from now (it will be sooner than you think!) you'll have a recorded body of personalized gardening information and memories that are far more precious and valuable to you than anything you can Google. In our home we celebrated the Lunar New Year this past week, so here's wishing you all peace and prosperity ahead! It's the Year of the Rooster, and our Henry just re-feathered and is looking particularly fine right now, as is appropriate. Hey, betcha thought a post in late December would be all hollyberries, evergreens and ho ho ho, right? Well, ha ha ha, I'm feeling the Winter Solstice and yearning for yellow as a reminder that sunlight hours will now start, ever so gradually, to increase. So let's take a look forward several months and think about plants that reflect the warmth and sunshine... it's never too early to plan for the season ahead! Colors in gardening cycle in and out of style, just as in the world of fashion. Blue flowers, white flowers, silver foliage... these classics endure perpetually. Red flowers always have fans, and there are gardeners who build their color schemes around the many shadings of purple, violet and magenta. And I've noticed that after years of being out of vogue, soft fleshy pinks are being snapped up by some of the most stylish nursery customers. Yellow, on the other hand, is something of a problem child. Many gardeners absolutely loathe yellow flowers... maybe they grew up with too many common, gaudy Marigolds or 'Stella d'Oro' Daylilies, surrounded tragically by yards of red mulch. Whatever the trauma, it's worth a rethink because for one thing, almost every plant comes in a yellow version. That means endless possibilities for creativity in an all-yellow scheme or one that uses yellow as a foil for other colors. Starting at the beginning of the season, spring bulbs are an easy antidote for the blues of late winter. Most of us grow and love Daffodils, and they come in every shade of yellow from ivory to egg yolk, but they're so well known that I won't discuss them here. Instead consider some other yellow spring bulbs, not so often planted but just as welcome. Species Tulips, like Tulipa dasystemon (left), are more reliably perennial than their taller, showier relatives and excellent for planting around and among emerging perennials. The Winter Aconite, Eranthis hyemalis (center), is always the earliest flower I have, popping up even before the Snowdrops and self-seeding in evenly moist soil where it's most happy. And the elegant Trout Lily, Erythronium x 'Pagoda' (right), is a vigorous hybrid that persists and blooms beautifully year after year in rich, moist soil. Really gorgeous paired with black-red Hellebores. Among the early blooming perennials are quite a few yellow options, these three for moist soil. Globeflowers, or Trollius (left), are Buttercup relatives that are available in yellows ranging from pale primrose to golden orange. They need consistent moisture and protection from hot afternoon sun, but when happy they will persist, and the tidy clumps gradually increase in size and can be divided after a few years. Primula veris, the Cowslip (center), is the easiest of Primroses and bulks up nicely, though not invasively, in moist shade. Can be divided every other year just after it blooms, and soon you'll have sheets of it in April. And if you have a pond, or a stream, or a bog, or even a ditch, you should be growing the Marsh Marigold, Caltha palustris (right), an American native with beautiful glossy foliage and sprays of golden yellow blossoms. Will grow right at the water's edge, provides early food for bees, deer resistant, self-sows to form a colony in time... what's not to love? For average to dry soil, in shade, I turn first to the Epimediums. Although they're pricey and slow to increase, they're worth the investment, spreading steadily to form handsome mats of weed-proof foliage after the flush of early spring flowers is past. Two good ones are Epimedium x versicolor 'Sulphureum' (left), and Epimedium x 'Amber Queen' (center), both of which increase as fast as can be expected for an Epimedium. 'Sulphureum' flowers at about 8" but 'Amber Queen' produces sprays of blossom a foot or more in height. A good companion plant is Helleborus x 'Yellow Lady' (right), happy enough in dry shade to survive and flower every year, but if you can enrich the soil just a bit, she'll put on a better display and increase more rapidly. Shrubs that feature yellow tones in spring are great as a complement and background for Daffodils and Primulas. Plant Forsythia if you must, but I'm content to enjoy it from a speeding car (local garden designer Heather Grimes calls it "The Vomit of Spring"). A much more interesting choice could be made within the genus Cornus, the shrubby Dogwoods. Cornus sericea 'Flaviramea' (left) is a yellow-twigged version of the native red-twigged Dogwood. Forms a nice colony in average to wet soil and bears fruits that feed the birds late in the season. Cornus mas (center) is a large shrub/small tree that blooms very early and sets pretty fruit that looks something like an oval cherry, edible but quite tart and used mainly for jelly in its native home of central and eastern Europe. And for a spectacular focal point in part shade, plant the variegated Pagoda Dogwood 'Golden Shadows' (right). Pagoda Dogwoods, properly Cornus alternifolia, are native to the northeastern US and so-called because of their elegant tiered branching structure. The yellow leaf margins of 'Golden Shadows' make it a standout in the shady understory it prefers, so you only need one! Yellow flowering trees are uncommon, so the debut of the yellow Magnolias was an exciting event in the world of horticulture. There are quite a number coming onto the market now, but the first of them was 'Elizabeth' (left), hybridized at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden by Dr. Evamaria Sperber in the 1950's. Just shows how long it takes many plants, particularly woody ones, to get from development into our gardens! 'Elizabeth' is a soft ivory color and very beautiful, but if you want a stronger yellow, choose 'Butterflies' (center), a nice primrose yellow, or 'Lois' (right), deeper still and a vigorous grower. Because of their parentage, many of the yellow Magnolias bloom a bit later than the pink and white cultivars, so they're less likely to be spoiled by late frosts. Euphorbias fill a lull in the season's flowering sequence: they come into bloom along with the later bulbs and remain attractive for a very long time, bridging the gap between high spring and early summer. They are primarily foliage plants, but I think their acid yellow flowers are a refreshingly sharp tonic to the soft colors of many spring bloomers. Most of the larger, dramatic Spurges (their common name) are too tender for us, so we can only drool over them in photos of English and Californian gardens, but the two above are reliable here and I wouldn't garden without them. Euphorbia polychroma 'Bonfire' (left) is a low mounder that stays tidy throughout the season, with colored foliage shading through wine red, bronze and even into tones of violet in the fall, always decorative and interesting. Sometimes tricky to establish (not sure why) but once it takes, it will be with you for many years. Marsh Spurge, Euphorbia palustris (center and right), is a much larger, shrubby cousin that's wonderful used in damp areas. Full sun will yield more flowers but it will also perform well in part shade. It's underappreciated because it looks a bit like a weed in a nursery pot, but once you see it well grown you'll be sold. Has a nice winter silhouette, too. Coreopsis, or Tickseeds, are an enormous tribe, and hybrids keep coming out every year in lots of luscious new colors, unfortunately not all of them hardy for us here in Zone 5. Three tried-and-true yellows though, are (left to right), 'Moonbeam' with delicate needle-like foliage and flowers a light, bright almost greenish yellow; 'Creme Brulée', with medium textured foliage and larger, butter yellow blooms; and Coreopsis tripteris, the giant of the family from the American prairies, sporting clouds of golden yellow daisies in September atop sturdy 6-9 ft. stems. No review of yellow-flowering plants would be complete without at least mentioning Daylilies. Enthusiasts go in for the newer pinks, lavenders and reds, but I'm still partial to a good classic yellow, especially when it has a high bud count and looks almost like a wildflower, like 'Wee Willie Winkie' (above). There are so many yellow varieties that you can plan a succession of bloom times to cover almost the whole summer. Other good yellows are 'Corky', short and floriferous with purple-brown buds, 'Berkshire Star', stately at 5 ft. tall with large golden flowers of a true lily shape, and 'Hyperion', the classic lemon yellow that's been popular since it was introduced in 1925. There's certainly no shortage of yellow daisy-form flowers, many of them American natives that are well adapted to life in our region. One year late in the season I asked local professional gardener Ruth Defoe how she planned to spend the winter, and she replied, "I'm going to finally learn the difference between Helianthus, Heliopsis, and Helenium!" A worthy goal, as they can surely be confusing. Helianthus 'Lemon Queen' (left), is super vigorous to the point of sometimes making a pest of itself, but in the right situation can be a real problem solver. Use it in semi-wild areas where it can be allowed to run rampant, out-compete weeds and cover itself with fresh lemon curd daisies for a very long period in mid- to late summer. Heliopsis 'Summer Nights' (center), is more mannerly, staying in a nice clump and attracting butterflies and other pollinators to its mahogany-centered flowers held on slim dark red stems. The foliage too, is suffused with a reddish tint, giving the whole plant a distinctive look. Best in full sun but will grow and bloom in part shade also. Heleniums come in some delicious shades of brownish red, copper and orange, but the pure yellows, like 'Kanaria' (right), are very useful too. Flat-topped clusters of cute little daisies with prominent button centers bloom for weeks. Older cultivars are very tall (up to 6 ft.) and may need staking, but the newer varieties are shorter and less trouble... just be sure they're sited in a moist soil that never dries out, or you will loose them! Otherwise very easy and rewarding. More yellow daisies, these all from the genus Rudbeckia! Just about every gardener has grown Rudbeckia 'Goldsturm', available everywhere, super reliable and floriferous... it's a gateway plant for novice gardeners and a workhorse for landscapers. Once you've cut your teeth on 'Goldsturm', you may want to advance to some of its more interesting cousins, all native Americans. Rudbeckia triloba, or Brown-eyed Susan (left), has smaller but profuse blooms that give a more delicate effect among grasses and other perennials. Sometimes short-lived but will usually self-sow, so you'll probably never be without it. Rudbeckia 'Herbstsonne' (center), is thought to be a hybrid between two species, but its origin in unclear. Nevertheless it's a big, beautiful plant with healthy basal foliage and flowering stems that rise to 6 ft. by midsummer producing, over a long period, bright yellow daisies with drooping petals surrounding a very prominent green conical center. My favorite is the giant prairie plant Rudbeckia maxima (right), the Great Coneflower or Cabbage-Leaf Coneflower, so called because its large, glaucous basal foliage does resemble a cabbage leaf. From the base, rigid stems ascend through mid- to late summer that bear the large-coned, yellow daisies. Best planted in groups as each stem may carry only one or two blooms, but unbeatable for providing a vertical accent among lower plants and grasses. All these Rudbeckias are easy, tough plants well adapted to our climate, great pollinator plants, and seed sources for native birds. To complement all those yellow daisies, something spiky is called for, and here's where we run into some limitations... I can only come up with three (ignoring the thuggish Lysimachia punctata!). Baptisias now come in lots of shades, and 'Carolina Moonlight' (left) is a very beautiful soft yellow. There are stronger yellows too, and lovely blends combining yellow with bronze or reddish purple, all of them extremely easy and long-lived American natives. Another great native is Carolina Lupine, Thermopsis caroliniana (center), a wonderful meadow plant that blooms in early summer and forms decorative seed heads that persist into winter. Finally, I have a sentimental attachment to Hollyhocks, and in spite of their tendency to succumb to rust and Japanese Beetles, I still grow them. The most reliable for me is the Russian Hollyhock, Alcea rugosa (right), a nice blendable lemon yellow that is fairly resistant to rust. Also seems to be more reliably perennial that most Hollyhocks, and there are always seedlings coming along in case the original plant plays out. Senna marilandica is a big, vigorous almost shrub-like perennial that has a slightly tropical look with its feathery pinnate leaves and clusters of bright pea-like flowers. Formerly known as Cassia marilandica, it's an American native that makes a bold statement used in a flower border, but you've got to stay on top of the seedlings that arise from the decorative seed pods. Used in a meadow, competition from grasses and other forbs will keep its progeny in check, and it provides a nice foliar contrast to most other meadow plants. Sedums are one of my favorite plant groups... easy, useful and rewarding. They flower in several colors: pink, purplish, white and yellow. I grow some of each color, but keep them carefully segregated because pink and yellow together sets my teeth on edge. Here are three good yellow-flowered types... Sedum kamtschaticum 'Weihenstephaner Gold' (left), an unbeatable weed-suppressing ground cover, Sedum kamtschaticum 'Variegatum' (center), a clumper with refined, cream-edged foliage, and a new favorite of mine, Sedum x 'Lemon Jade' (right). It's a taller plant, similar in scale to the popular 'Autumn Joy', but reliably upright and opening soft primrose yellow from broccoli green buds. The subtle color makes it easy to combine with other late blooming perennials and it looks particularly nice with the seed heads of grasses like Pennisetum 'Hameln' or Bouteloua 'Blonde Ambition'. Goldenrod, properly Solidago, is a genus well represented in North America with over 100 different species native. Many are so common on roadsides and abandoned fields that it seems unnecessary to include them in our gardens, but here are a couple that are refined and distinctive enough to merit domesticity. Solidago rugosa 'Fireworks' (left), makes a bushy clump, vigorous but not invasive, that explodes in late summer into a shower of golden wands. The effect is quite delicate in spite of the gutsy color, and it makes for a good contrast with Asters, Boltonias and the flowering grasses. Very attractive to bees and butterflies, and tough as nails. Completely different is Solidago caesia (right), the Blue-stem or Wreath Goldenrod. It grows low and spreading, flowering all along its almost horizontal stems. Particularly useful for dry, partly shaded locations where the range of plant options is always limited. It must be mentioned that many people still believe that Goldenrods cause hay fever, but this is simply not the case... Ragweed, which blooms at the same time, is the real culprit! With a little imagination you can create satisfying combinations using just shades of yellow and yellow-green foliage. This grouping, at the former Loomis Creek Nursery, includes yellow Violas, Verbascum chaixii, a golden conifer, a variegated yellow-twigged Dogwood and some California Poppies. The silvery plant behind is the giant Scotch Thistle, Onopordum acanthium. There are, of course, many more yellow plants... we've only scratched the surface here. And I'd love to hear from you if you have a favorite I've left out. I hope you've enjoyed this dose of sunshine in the midst of the shortest, gloomiest days, and whatever holidays you celebrate, here's wishing you joy and peace and warmth to come. Yes, Gentle Readers, it's been a very hot summer with record temperatures and less than average rainfall, coming on the heels of an almost snowless winter. Ground water is depleted and gardeners as well as plants are feeling stressed, tired and wilted. But we soldier on, resilient and ever hopeful... that's part of what it means to be a gardener! Like a crisp linen shirt, white in the garden can be a refreshing and revitalizing antidote to the sultry weather. There are many choices with either flowers or foliage in shades of white to help alleviate the heat, at least visually. Here, a few of my recommendations... The Bottlebrush Buckeye, Aesculus parviflora, is one of our most magnificent native American shrubs. Grows 6-12 feet tall and forms a colony of stems in time, but never invasive. Best in rich soil and part shade, it seldom needs pruning and and is almost never troubled by pests or diseases. The panicles of tubular white blossom attract butterflies when they appear in July, and the handsome palmate foliage turns buttery yellow in fall. Its native range is the southeast US but it's perfectly hardy all through USDA Zone 5. Underappreciated, but highly recommended. Oh those botanists! I still keep calling this Cimicifuga racemosa, but it's now Actaea racemosa. Nonetheless, one of the best late-blooming perennials for shade, and a native as well. Curvaceous spires of fluffy white flowers soar as high as seven feet on strong slender stems, carried well above the mounds of ferny deep green foliage. Needs at least average moisture to thrive but really at its best in an area that never dries out. This is a plant with some fascinating common names: Bugbane, Snakeroot, Black Cohosh, based on medicinal and insecticidal qualities of the rhizomes and their reptilian appearance. I just think it's a wonderful architectural perennial that's valuable for blooming so late in the season. In addition to the plain green species, there are quite a few selections with darker, purplish foliage that are even more decorative. Cornus 'Ivory Halo' is as cool in summer as it is warm in winter, thanks to its clean, white-margined leaves that unfold as the bright red twigs fade with the coming of spring. The red- and yellow-twigged shrubby Dogwoods are popular for their beautiful stems that show up so nicely against the snow, but most of them inspire very little interest once they leaf out. Not so with this one, a variety of Cornus alba, the Tartarian Dogwood. Easy to grow and will mature to 6-8 ft, although it can be kept smaller with pruning, and it's advised to remove about a quarter of the stems each year to encourage new shoots, which have the best winter color. The flowers aren't much to rave about, but the fruit is very attractive to birds, and the fall color is often quite good. Hydrangea arborescens 'Haas Halo' is the lacecap cousin of the widely planted 'Annabelle', but I think much more elegant. The 14" wide blossoms are carried on sturdy stems 3-5 feet tall with deep green, glossy foliage, and because it's a seedling of the native Smooth Hydrangea, its refined appearance is backed up by a very tough constitution. Makes a stunning mass planting or a beautiful specimen, and the flowers are popular with honeybees and other pollinators. They also dry well, or if left on the plant through the winter, look wonderful dusted with snow. One of the longest blooming perennials, Calamint (Calamintha nepeta ssp. nepeta) is the perfect choice to face down taller plants at the edge of a border, or lovely used in mass on its own. Low bushy clumps--not invasive like the true Mints--flower from June until September with clouds of tiny, white or ice-blue blossoms adored by honeybees. The foliage is delicate and extremely fragrant when crushed or even brushed against, adding to its cooling properties. A real workhorse in the landscape with a lot of airy charm to boot. Miscanthus sinensis 'Cosmopolitan' is one of several white-variegated Maiden Grasses on the market ('Cabaret' and 'Variegatus' are also good choices). Tall and stately with beautiful arching foliage edged in creamy white, 'Cosmopolitan' looks great with large scale perennials and can hold its own as a contrast and complement to shrubs. Like all grasses it adds movement to any planting, and will fade to shades of golden tan and look good well into winter. Needs adequate moisture to establish but otherwise trouble free... just be sure to cut it down early in spring so the sun can warm the roots and encourage strong new growth. Early summer is the flowering time for Viburnum plicatum 'Shasta', but it looks wonderful all season long and is so useful as a large screen I couldn't help including it in this list. Lacy flowers carried on elegantly layered branches are followed by small fruit that Robins love and clean foliage that turns shades of russet in fall. Best with reliable moisture, but will thrive in average soil as well, in sun or shade. A great, dependable shrub that can block out an unsightly neighbor in just a few seasons! Liatris spicata is commonly seen in purple, but 'Floristan White' is a variety I've come to love. This native's fluffy wands open from the top down, while most flowering spikes open from the bottom up, and it increases reliably every year, forming something like a corm at the base of the stems that can be easily divided to increase your stock. The spikes turn a pleasing shade of tan and remain decorative through the winter. Versatile Liatris looks equally at home clumped in a traditional flower border or scattered throughout a grassy meadow planting. Border Phlox (Phlox paniculata varieties) have been around since Victorian days and although they're sometimes martyrs to mildew and viruses, I'd find it hard to garden without them. No other summer perennial has quite the visual impact, or the delicious fragrance, especially notable in the white varieties. 'David' and 'Volcano White' (above) are two cultivars I grow, and both have improved disease resistance. One key to success is to keep them consistently moist, easier said than done in a summer like this one, but well worth the effort! Oakleaf Hydrangea, Hydrangea quercifolia, is one of the crown jewels of American native shrubs. Easy to grow with beautiful foliage, gorgeous flower panicles, spectacular fall color and interesting exfoliating bark, this is truly a four-season plant. Its only drawback is that deer absolutely maul it in the winter, so site accordingly, net it, or spray and pray. How can you resist this fall color? One of my favorite native perennials, Eryngium yuccifolium grows roadside in the Louisiana pinelands where I grew up. The greenish-white bobble flowers are carried in branched clusters on tall stems above jagged grassy foliage that forms handsome clumps about the size of a Daylily plant. The folk name of this plant is "Rattlesnake Master", a reference to its supposed ability to cure snakebite. I'm happy just to grow it for its interesting texture and decorative winter seed heads! Perfectly hardy in the Hudson Valley given good drainage and full sun. Another terrific native perennial is Culver's Root, Veronicastrum virginicum. Its tall, elegant habit lends needed verticality to perennial borders, but it looks fantastic in a meadow planting as well. Easy to grow, low maintenance, adaptable to most soils from average to wet, and attractive to butterflies and other pollinators. There are lavender cultivars on the market but I think their color is a bit washed-out, so I much prefer the clean white one. Blooms July into August, above pretty whorled foliage, and the spent flowers look interesting all through fall and winter, so no need to deadhead. The White Turtlehead, Chelone glabra, is a lesser-known native perennial but one you might spot in low wet areas or even roadside ditches anywhere in the Hudson Valley. The common name comes from the unusual shape of the flowers, said to resemble a turtle's head, and the genus name is derived from the Greek chelone, meaning tortoise. Beautiful in a bog garden or at the margin of a stream or pond, where it can get the regular moisture it needs. Otherwise trouble-free, cool and lovely in late summer. Summersweet is the common name for Clethra alnifolia, and a good name it is too, for no other American native has such a heavenly scent when in bloom. The panicles of flowers are irresistible to butterflies and honeybees, and are followed by bead-like seed heads that remain attractive into winter. Deciduous foliage that's a fresh green all summer, turning golden yellow in fall. Suckers to form colonies and happiest with damp feet and its head in the sun. There are pink-tinged varieties too, all fragrant and lovely. The Mountain Mints, Pycnanthemum species, are enjoying quite a vogue right now among gardeners who've discovered them, and I recommend you try this one if they're new to you. It's Pycnanthemum muticum, aka Short-toothed Mountain Mint. The silvery bracts that surround the true flowers make landing pads for a whole menagerie of pollinators: butterflies, bees, moths, beneficial wasps and more. Makes a great cut flower too, lasting weeks in a vase, and the foliage smells deliciously of pennyroyal. Even though they're called "mints", there's no need to be alarmed... they are vigorous native plants but not nearly as aggressive as the culinary Mints. A sunny spot with good drainage is the perfect home for Silver Sage, Salvia argentea. Huge furry lobed foliage like Lamb's Ear on steroids, and it blooms early in the summer with a big spike of white flowers. Not a long-lived perennial but I've had excellent results keeping it going by mulching with gravel and removing the bloom spike after flowering to prevent seed formation. A real eye-catcher in the perennial border or rock garden, and children love to pet it! One of the big guns of late summer is the Pee Gee Hydrangea, Hydrangea paniculata 'Grandiflora', a classic shrub first introduced into cultivation around the time of the Civil War. There are now dozens of varieties, in all sizes, and sold as shrub forms or standards (above) which are often called "Tree Hydrangea", a misnomer. All of them are beautiful, reliable shrubs for our climate, winter hardy and floriferous, only requiring decent soil, reasonable moisture and a modest pruning job every spring before they leaf out. 'Bobo' is a Hydrangea paniculata variety recently introduced from Belgium, and its compact size (under 5 ft.) makes it more manageable for many situations. Plus it's a prolific bloomer. Almost all the paniculatas start out white and turn shades of pink as fall approaches, and 'Pink Diamond' is one of the prettiest that colors up well, and has open panicles that fit better into naturalistic settings than some denser-headed cultivars. In fact, there's a Hydrangea paniculata variety for just about every taste, from beach-ball sized heads ('Phantom') to elegant attenuated lacy sprays ('Kyushu) and everything in between. I hope you've enjoyed my list of summer coolers... I'm sure you have some favorites of your own that I passed over. The goal is to make our gardens enjoyable, personal and inspiring, even in the most trying weather! Confession: I never cared much about Crabapples, neither liking nor disliking them to any great degree. They were another spring-flowering tree commonly seen on neighborhood front lawns, like Dogwoods and Redbuds. Pretty, but nothing remarkable. Then I inherited one at the house I bought. It was planted about ten years prior by the two spinster sisters who lived here, and who had an infallible sense of what would look just right at this funky old farmhouse. Taken out of its suburban setting, near our clothesline and on the route we take, twice daily at least, out to the henhouse and vegetable garden, it seems perfectly suited and has reached a stage of maturity that's allowed me to fully appreciate its year-round appeal. I have no idea what the variety is, but like most Crabapples it flowers in May, its deep pink buds opening gradually to become a fragrant cumulus cloud of white blossom, alive with bees and other pollinators. The big display lasts for the better part of two weeks, longer if the weather is cool and overcast, and as the petals drop they litter the ground underneath in a charming way, competing with the white Crested Iris and white Epimediums I've planted in the tree's shade. Throughout the summer months it remains a substantial but unobtrusive presence that, along with two ancient Lilacs, makes up the canopy of a large shady area that's ideal for Hellebores, Hosta, Hakonechloa, Asarum and many other herbaceous plants. Its leaves are handsome, clean, glossy and (so far) disease free, so I suspect it's one of the more modern varieties that are being bred for greater resistance to the many problems that plague fruiting apples. But make fruit it certainly does, thousands of pea-sized bobbles that cluster densely on the branches and mature to a deep ruby red by fall, and hang on through most of the winter until, sweetened by multiple frosts, they're stripped by Robins, Cedar Waxwings and Jays. Even after the fruit is gone, our tree gives us pleasure with its gnarled, mature structure and dense twiggy branches. Choosing a Crabapple variety for planting can be a daunting task as there seem to be hundreds in cultivation, but if your home's style is farmhouse casual, stick with the white-blooming cultivars. 'Donald Wyman' (below) is a reliable, disease resistant choice with a handsome form, profuse flowers and small, bright red fruits. If attracting birds is a priority for you, make sure you choose a type with fruit on the smaller side... under one inch in diameter. If you're interested in cider-making or jelly (Crabapples contain high amounts of pectin) there are larger fruited varieties too. If you have a more formal or modernist property, you might consider a variety with brighter flowers and colored leaves, like 'Centurion'. The deep rose-pink blossoms are followed by purple new foliage that turns a rich bronze-green as the season progresses. These are more "gardenesque" types that can be used to great dramatic effect, as in the grove planting (below) designed by Peter Bevacqua. An allée of them would also be spectacular. For the truly romantic, 'Red Jade' (below) is a beautiful weeping form that looks right as a featured specimen with Gothic Revival, Victorian or Asian-inspired architecture. The white flowers are followed by deep crimson, jewel-like fruit about 3/4" in diameter. Whatever your taste, there's a Crabapple that would suit the bill, and I urge you to rethink their appeal. Hardy, reliable and beautiful in all seasons, they need to be reconsidered and used more carefully and creatively. Like the potato in cooking, they can be down-home unpretentious or dressed-up sophisticated, a very useful staple that deserves being seen through new eyes, and freed from the cliché of suburban overuse. |

Welcome to Sempervivum, an opinionated, sometimes informed and completely unqualified journal of gardens, plants and plantings by artist-gardener Robert Clyde Anderson. Archives

October 2021

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed