|

I said I wanted more sunlight . . . but not like this. Every gardener's year is full of ups and downs, nice surprises and dismal failures, glowing magical days and challenging weather events. We had one of those events last week, a big blow of a storm that brought down two large trees on our neighbor's lot ... a huge pine that smashed his garage and damaged his vintage Corvette, and a fifty foot willow that so conveniently fell right onto my wet meadow planting. (Yay!) This part of the planting is mostly indestructible herbaceous things like Rudbeckias, Asters, Filipendulas, Eupatoriums, and tough Switchgrasses and Big Bluestems. But there are also mature specimens of 'Skyracer' Moor Grass just coming into its fall glory, and a nice group of three 'Winter Gold' deciduous Hollies, covered in still-green fruit and finally showing a substantial presence after five years in the ground. The Willow also brought down my neighbor's power lines, which meant I couldn't even get in to assess the damage until the utility crew arrived to free the wires. So what the tree didn't flatten, the utility guys managed to stomp down in their chain-saw frenzy. MEN AT WORK! ugggh. Trying to look on the bright side . . . perhaps some voles were crushed? Of course everything will grow back in time, but the loss of chunks of woody screening is a bit depressing. This Viburnum trilobum took quite a lick, and one of the Winterberry Hollies was badly damaged; the other two just dodged the hit. Elsewhere in the garden, there was flattening of perennials and grasses, even normally sturdy plants like this 'Northwind' Switchgrass. A week later, most of them have already partially recovered, and will become even more upright as they dry out in the fall progression. The Dahlias blew over, but that was mostly my fault. . . I got cages on but failed to put the stakes in before we went on vacation in July. They've been righted and they're fine now. Remarkably, our two massive Silver Maples came through with just the loss of a few relatively small branches, and a couple thousand twigs. Could have been much worse. And the week before, we had such a beautiful Labor Day weekend with our Pop-Up Open Garden and Tag Sale. Lots of folks came, and we had a blast meeting new people and seeing dozens of old friends.

Coming on the heels of a summer filled with massive, tragic natural disasters, we feel humbled and relieved that there was no worse outcome. Our neighbor is safe and the plants will regrow. Yesterday, Kuan and I were able to clear almost all of the tree and get it stacked by the road for the town crew to haul away. Things are returning to normal. Still, these garden tragedies are challenging, but all part of life as a gardener. Each year brings its share of delights and disasters, and we learn to roll with them. They all remind us of the fragility of our little creations, and of our life itself.

4 Comments

Getting Two Seasons of Interest from One Area Seeing this area of our garden come into full maturity has been very gratifying, although speaking of any planting as "mature" implies that it's finished, which is never the case. Constant change, evolution, mutation... these are the qualities of all plants, and therefore of all gardens. Which is why I'm often amused by the drawn plans of garden professionals whose carefully thought out and beautifully rendered placements of each perfectly circular plant should be taken with a very large grain of salt. Plants grow and increase. Or they dwindle and die. They invade, overtop, weave about, pop up unexpectedly. They can smother their neighbors, or grow up through them in a mutually beneficial arrangement that you never thought of facilitating. In short, they move. That's why in my talks and classes I point out that garden design is more like choreography than it is like painting. The elements of time and change are always present. Designing our plantings so we get two peak moments from each part of the property is an ongoing goal of mine, and I think it's achievable for many home gardeners. We call this area the dry terraces, because they're on the south side of the house in full sun, and our soil is light sandy loam. When we bought the house it was a weed-infested bank too steep to mow safely, so we carved out three levels of beds and built our own low retaining walls and steps. It seemed the perfect place to grow sedums, lavenders, verbascums, and lots of other plants that like to bake in the summer. Almost by accident I discovered that tulips also thrive in those conditions, so the opportunity presented itself to make a bright spot in mid-spring. Here's almost the same view as the photo above, taken in late August. Completely different textures, density, and color scheme from what happens at tulip time. Looking up the terraces in late April . . . . . . and the same view at the end of summer. Everything here is perennial; in this photo there's Lavender 'Hidcote', Calamintha 'White Cloud', Allium 'Millenium', Garlic Chives (Allium tuberosum), Sedum 'Lemonjade', Salvia 'Berggarten', Bouteloua 'Blonde Ambition', Sporobolus 'Tara', and various small creeping Sedums. By mid-April, most of the perennials have emerged and the earlier tulips are blooming. The carpeting plants, like Sedum 'Angelina', Sedum 'Voodoo', Veronica 'Tidal Pool', and Pussytoes (Antennaria plantaginifolia) all play a large role in filling the gaps between the crowns of the larger herbaceous plants. You can see grasses and alliums emerging here, among the earliest tulips. I plant a mix of species tulips and large-flowered hybrids, set deeply in the fall to encourage them to perennialize. Even so, I only get about half to settle in for more than one year, so adding a few more of my favorites every fall keeps the display going. Dotted throughout are plants of my favorite spring perennial, the Red Pasque Flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris 'Rubra' (lower left). Its charming wine red flowers are followed by fuzzy, decorative seed heads. They self-sow here and there, in favorable years. My go-to species tulip is the easy and reliable Tulipa orphanidea 'Whittallii'. Its coppery orange blooms have a center of olive green, black, and gold... an unusual and striking color combination. They're relatively inexpensive so I've planted them generously, poking the bulbs right down into the mats of Sedum 'Angelina' and the other carpeting plants. The Creeping Phlox is one I've had for many years, 'Oakington Blue Eyes', and I love the way it contrasts with all the warmer tones of the tulips and sedums. In addition to the small species tulips, I also plant a few varieties of the large standard hybrids, my favorite being this one, 'Brown Sugar'. They are less reliably perennial, but you can't beat the impact they have with their large flowers in delicious, rich colors. Here you can see a clump of Allium 'Millineum' emerging with its fresh dark foliage, and silvery Pussytoes coming into bloom just behind. Another favorite is this vintage 1911 variety, 'Dom Pedro'. Its flowers age from a deep plum to coffee brown, and it's been reliably perennial. Behind it you can see fresh mounds of Calamintha 'White Cloud', and the vigorous foliage of Rattlesnake Master, Eryngium yuccifolium, which will become quite a large feature in summer. Other darks come at the end of tulip season, like the popular 'Queen of Night', and overlap with some of the late daffodils. By the end of summer, the stone retaining walls are almost obscured by the perennials that thrive in the perfect drainage and hot sun. There's actually a large range of plants that like these conditions, so it's been a challenge to limit myself to a palette that allows for sizeable clumps and repetition throughout the three levels. At the top, a large old Rose of Sharon and a compact Buddleia 'Butterfly Heaven' provide some woody heft. Over the years these plants have settled in, merged, and meandered to completely cover the soil, allowing little space for weeds to sprout. This idea of a weed-resistant tapestry or mosaic of plants is one of the foundational principles of naturalistic gardening, a version of ground cover that uses a combination of several plants rather than a monoculture, what garden designer Claudia West means when she says, "the plants are the mulch". Most of the flower power of this second peak is provided by the late alliums. They're less familiar to most gardeners than the large spring-blooming varieties, but don't have the annoying habit of dying foliage just when the blooms are at their best. The purple balls of Allium 'Millenium' and its vigor and reliability make it one of my favorite perennials of the last twenty years. I also love the white Garlic Chives, Allium tuberosum, for its height and willowy stems. It must be relentlessly deadheaded after flowering, or it will seed everywhere, but I think it's worth that trouble. Although most of the plants in these beds are under a foot in height, I've planted a few taller species to provide some contrast. Here, in the lowest terrace, are a few large clumps of Rattlesnake Master, Eryngium yuccifolium, and a favorite Switchgrass cultivar, 'Ruby Ribbons'. In the lower right corner you can see a couple of the vibrant magenta-rose flowers of Wine Cups, Callirhoe involucrata. From a parsnip-like root, it throws out long trailing stems covered in flowers that light up the terraces in June and July. All three plants are natives which have evolved to tolerate our hot American summers that often have lengthy dry spells. I have a few more areas of the garden where I'm trying out this two-seasons-peak idea, but I'll save those for another post. Meanwhile, I hope you're inspired to try some double-dipping yourself, horticulturally speaking. It's fun to find plants that fit into this scheme, and gratifying to see them thrive and provide interest for more than one moment in the gardening year. So try it yourself . . . I think you'll enjoy the challenge.

Our property isn't a showplace. There's no historic house, no magnificent view, no fashionable potager. There isn't a pedigreed design from a noted garden architect. No fountains, parterres, pergolas, conservatories, follies, or grottoes. There is a "ruin", but we call it the house and we live inside. Architecturally, it's a Frankenstein's monster... at core an 1860's farmhouse, but with handyman accretions and additions built on by one extended family over the past hundred years. A realtor friend of mine once described it as "the ugliest house in the county"... which I guess is a distinction, of sorts. So I've been somewhat reluctant to open the garden to public view, despite having been asked several times. I don't want visitors, who've paid a fee, to be disappointed and leave thinking they were let down. Recently, however, I've begun to relax and realize that perhaps there's something of value to be seen here after all, not for those looking to be wowed, but for those deeply interested in plants and their cultivation. I've always considered this garden a laboratory for my own passions and obsessions, so there are many varieties of shrubs, grasses, and perennials planted here. It's a constant challenge to balance the collecting urge with a desire to have everything hold together into a cohesive vision, with a sense of being in a garden rather than a nursery's back lot. And I've never been a person who swept the canvas clean when moving into a new place, so there were many plants (mostly trees) that I tried to retain from previous owners. But slowly, over ten years, it's evolved into something like my own vision of what this garden can be. The word that keeps coming up from visitors here is "relatable". At two acres, the property is larger than most suburban lots, but still manageable for us. We have no outside help, but big areas are occupied by the outbuildings, parking court, and the large front lawn. The garden beds are mostly close to the house, but there's a large swath of naturalistic planting along one side of the property that extends as far as the road. There's a sunny dry terraced bank, a moist and shady streamside planting, and other assorted micro-ecologies that offer a variety of conditions suitable for a wide range of plants. So it seems that most people, especially plant nerds, can find something of interest that relates to their conditions and particular horticultural tastes. Also, our standards of maintenance are anything but perfection... again, relatable. The two open garden events I've hosted have been for groups of fifteen to twenty people, almost all of them experienced, passionate gardeners. They appreciate hearing the travails of another enthusiast, both my successes and my many failures, misfires, and disappointments. Here I can show them areas that are thriving, but others in need of some improvements I haven't quite figured out, or projects abandoned through boredom or lack of time. Instead of being designed and executed by professionals, this garden has grown and developed over time, along with my own knowledge and tastes, a process that all amateur gardeners understand. Most people who visit gardens are quite civilized and extremely polite. If they were horrified by anything here, they were certainly diplomatic enough to smile and keep it to themselves. But judging from the comments, questions, and follow-up thank-you notes, most of our guests came away with some knowledge or insight they didn't have before. Whatever inspiration visitors may have derived, the benefit to me was far greater. I loved having so many different and knowledgeable sets of eyes on my efforts. Having been to art school, I take critiques well, so any and all comments were appreciated. It's remarkable how perceptive and helpful another person's vision can be, especially when I respect their chops as gardeners. Plus, it's just damn fun to hang out with other plant enthusiasts, geeking out on the finer points of Panicums, or discussing which cultivar of Physocarpus is most mildew resistant, or bashing the botanists for splitting the genus Aster. So take my advice... if you're asked to open your garden for a couple or a couple dozen, please do so. I don't think you'll regret the experience, and you'll definitely gain more than you lose through anxiety about how your place looks. Trust me... gardeners are kind, gardeners are forgiving, gardeners are superior people. Let them in, and learn from them. I forget how magnificent our big Silver Maples are, until someone like friend and colleague Dorthe Hviid reminds me.

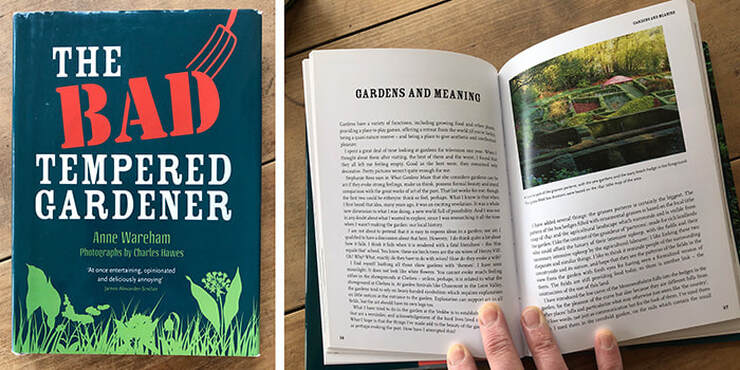

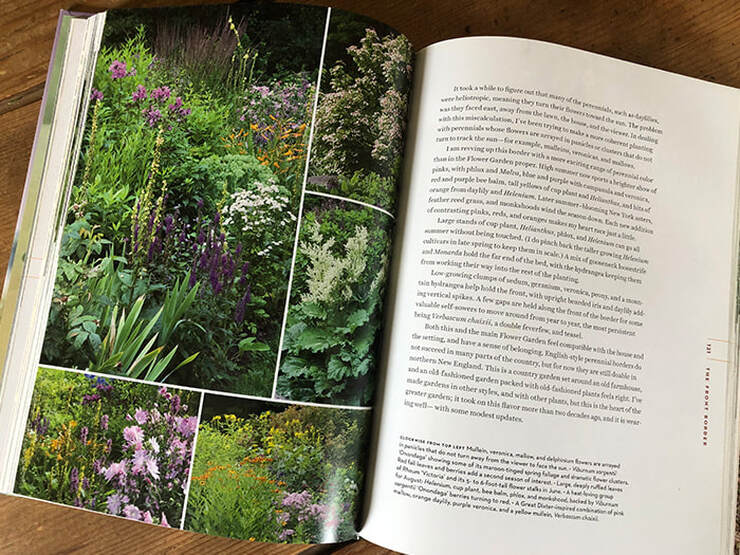

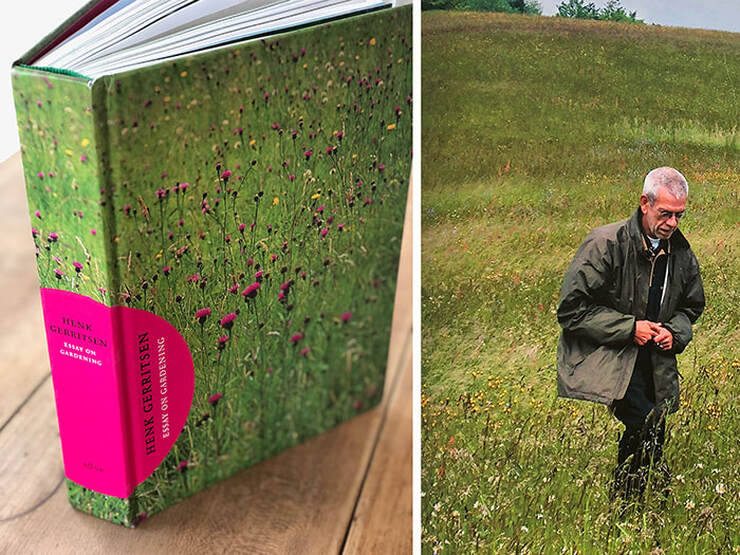

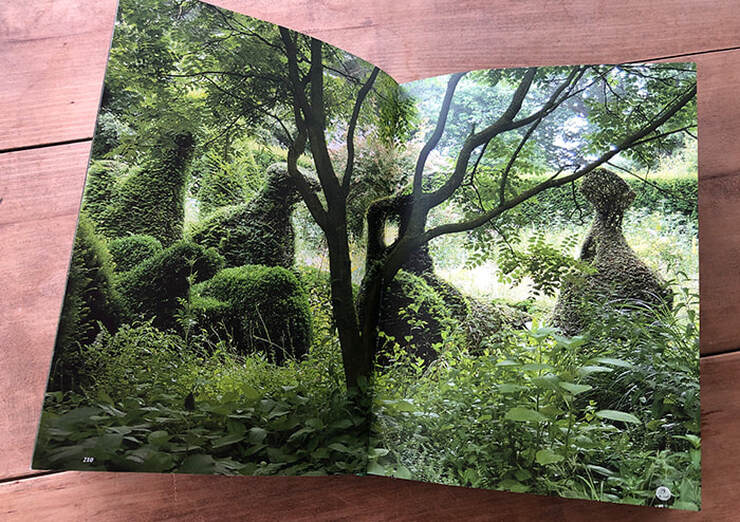

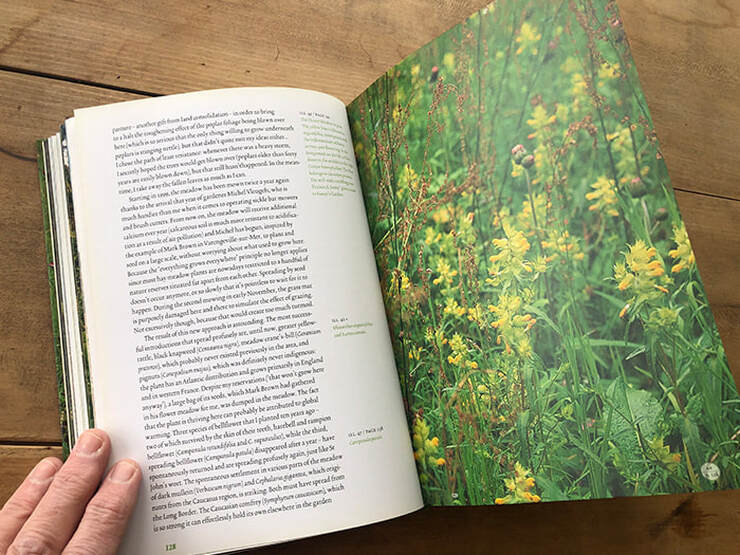

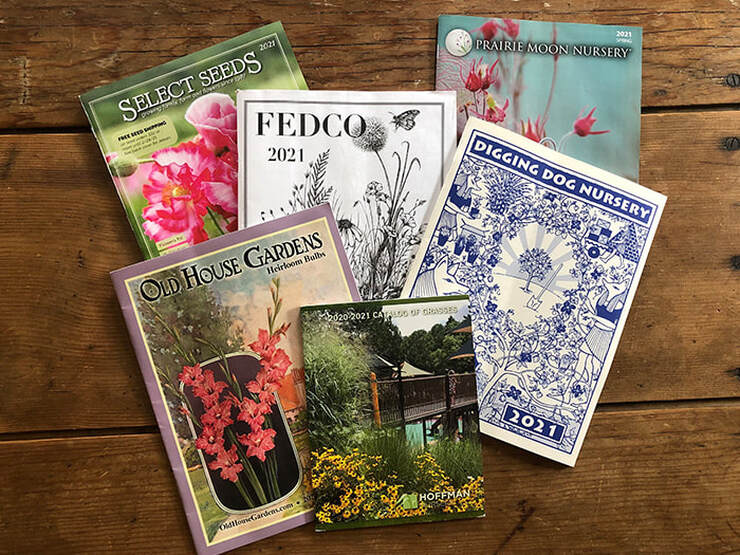

Winter, for gardeners in our climate, is a time of blessed rest. But also planning, scheming, and above all, reading. This year I’m making a conscious effort to delve back into my actual books, a pretty good collection that’s been assembled over the last thirty-odd years and recently gets neglected in favor of the quick google when a question arises. I do regularly read a few garden blogs, many of them written by people with distinctive voices and years of expertise. My Instagram follow list is mostly British and German gardeners, with a smattering of French and Portuguese and even Russians… Americans too, of course. The internet is great for keeping up with what’s current in the world horticulture scene, but the information often seems so fleeting, and sometimes so superficial. Returning to the bookshelves, and the bookstores, has been nourishing. So here’s my winter reading list, so far… The Bad Tempered Gardener by Anne Wareham A book I’ve had for several years (it was published in 2011) but never got around to reading… and my loss, because what a challenging, maddening, inspiring writer she is. The mistress and creator of “The Veddw”, a well-known garden in Wales, Wareham pokes holes in many a sacred garden cow: plant obsession, television gardening personalities, open garden days, roses…just a few of the topics she skewers with wit and intelligence. Her willingness to question established norms is refreshing, and a sampling of some titles from this collection of essays will give you an idea of their scope: “I Hate Gardening”, “Are Gardens for Gardeners?”, “Sharing a Garden”, “Status”, “Roses and Taste” to name a few. Her irascible style brings to mind the late, great Christopher Lloyd’s writing, tempered with a healthy dollop of self-deprecation. She made me think, and re-think, some of my long-established ideas. She’s like that long-time friend you have who knows how to push your buttons in an infuriating way… but in the end you know she’s right. Spirit of Place by Bill Noble A book that was much talked about and promoted last spring, written by a well-known professional gardener and former director of preservation for the Garden Conservatory. It documents the creation and evolution of his property in the Upper Valley of Vermont, an area I know a fair amount about, having visited friends there many times. So I was interested to read it. Still, it took me three tries before I was engaged enough to finish the book… the first chapters seemed a replay of a planting style, and a plant palette, that were popular twenty years ago. Plants like Hydrangea paniculata ‘Quick Fire’, Sedum ‘Autumn Joy’, and Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ were thrilling us back at the turn of the century. Now, not so much. Reading further, I began to appreciate his very deep and broad knowledge of plants, and to marvel at the collection he’s assembled of really the best of the best shrubs, perennials, and alpines that are hardy in a challenging northern climate zone. And I acknowledge that the garden was, after all, started more than twenty years ago. My own garden being now just half that age, it’s encouraging to see how two decades of growth pays off in the maturity of established plantings. This is definitely a plantsperson’s book… beginners will be daunted by the cascade of Latin names and comparison of cultivars and subspecies, although they may enjoy the many good photographs. In the end I found it to be an enjoyable read but one that chronicles a collector’s, rather than a designer’s, taste. Much of the book is a bed-by-bed documentation of plants therein… interesting enough for plantaholics, but hard to follow without constantly referring back to the plan on the endpapers. I longed too for more of Mr. Noble’s personality to shine through, and to visit his garden to see the plantings first-hand… he seems like a nice fellow, and acknowledges towards the end of the book that “much of the garden is outfitted with old-fashioned plants and garden styles not currently in fashion”. That raises the question of what our current horticultural obsessions will look like in twenty years…and whether they will age as gracefully as this solid assembly of top-notch cultivars in his garden has done. Essay on Gardening by Henk Gerritsen Much more congruent with my own curmudgeonly gardening temperament is this book I’m actually re-reading, for the third time I think. Henk Gerritsen is one of the founding figures of the “Dutch Wave”, but little known in this country, partly because he was more of a writer than a designer, and partly because he died at a relatively young age. But he penned several early books with Piet Oudolf, as well as this one, his definitive collection of thoughts on nature, ecology, and gardens. Gerritsen’s original obsession was with the wild plants of Europe, and he only came later to be interested in gardening, creating with his partner Anton Schlepers an idiosyncratic and influential garden they called Priona. This is a book that’s perfect for the bedside… there’s no straightforward narrative line, so you can dip in and out of it at will. And his take on things horticultural is often challenging, always thoughtful, and usually witty. A couple of quotes… “Gardening is the most elusive of all the fine arts. The art of gardening uses living material, which has its own laws and prerogatives and which won’t allow itself to be manipulated by the artist without a struggle.” Regarding weeding, he writes… “I know quite a few gardeners who with satanic pleasure dedicate every free weekend to committing a veritable bloodbath in their garden, so that they may maintain their air of pacifism during the week. And what of the weeds? They lived happily ever after…” Indeed, Gerritsen has been perhaps the main proponent of what is disparagingly called “the weedy aesthetic” by those skeptical of the current trend towards naturalistic planting. But in his case the scruffiness of his garden seems the result not so much of laziness but of his extremely deep knowledge and appreciation of wild, atypical, and species plants. I haven’t had a chance to visit the Priona Garden, but from the many photos in this book it appears that the lavish wildness is balanced by a thoughtful use of topiary, hard paving, and other kinds of structure that act as a design counterpoint to all the effusive planting. This is also one of the most beautifully designed gardening books I’ve seen recently, and at almost 400 pages, it’s packed with challenging ideas and practical information, especially regarding plant communities and habitat archetypes. If you’re seriously interested in ecological gardening and naturalistic planting this is a must-read, seminal work on the subject. Plant Catalogs Printed nursery and seedhouse catalogs, once one of the mainstays of a gardener’s winter reading, increasingly appear to be going the way of buggy whips and eight-track tapes. There used to be so many good ones from small, family-run nurseries, packed with opinionated takes on everything from trees to rock-garden plants. Now we’ve lost dozens of those independent outfits, and the ones that remain find it harder to justify the expense of printing and mailing a paper catalog. And who can blame them. But they are sorely missed, particularly those book-sized inventories dense with text and nary a photo, like Forest Farm’s (still sent out but much reduced) or the fantastic descriptions detailed by Dan Hinkley for Heronswood Nursery. (Once, on the train up from the city, I accosted a woman who was reading the Heronswood catalog and we happily nerded out on plants for the rest of the trip). There are still a few printed catalogs left, for now at least, that make good reading… Select Seeds, Old House Gardens, and Prairie Moon Nursery all present accurate information illustrated with attractive photos. My go-to for vegetables and some unusual flowers is the Vermont company Fedco. Their thick newsprint catalog is full of information and opinion, and they send larger quantities of seed for the price than anywhere else I’ve found. And for perennials, I love Digging Dog in northern California. Though many of their plants are Zone 6 and warmer, they list enough desirable Zone 5 selections to keep me coming back year after year. And a new one that’s really a great reference is the ornamental grass catalog of Hoffman Nursery in North Carolina. They’re a wholesale grower, so I’m not sure the catalog is generally available, but if you can get your hands on it you’ll be fascinated by all the selections described (35 varieties of Carex! With a comparison chart!) * * * * * * * * * Here in the Hudson Valley, the Witch Hazels are blooming and the snow is retreating, but there are still many chilly evenings available for snuggling down with a good, old-fashioned book. I hope you’ll rediscover some of your favorites, and find a few new ones to keep you occupied. That is, until the longer evening light and increasingly warm temperatures of spring seduce us into spending those evenings actually gardening. Oh Gentle Readers, I’m sure most of you will agree that 2020 is a year we’ll be happy to see pass into history. Pandemics, fires, hurricanes, elections… well, you know. On top of which I’ve had some difficult challenges in my personal life that absorbed most of my free time. So despite good intentions, my ability to write about plants and gardening here has been severely curtailed by lack of time, energy, and focus. But the gardening itself has been a great source of solace for me throughout, as it has been for so many others. More time at home has meant more people discovering, or rediscovering, the pleasures of growing and caring for plants. Nurseries, it seems, are one of the few businesses that had a banner year. Looking back at my own photos from 2020, I’m reminded of the high points, discoveries, revelations and just plain old comforts that my garden has given me. So to wrap up the year, a few thoughts about plants and plantings that inspired, charmed, or surprised me, and kept me going through the last growing season… Our first flower of 2020 was the little rock garden Iris ‘Katherine Hodgkin’, always a welcome surprise to see emerging from the leaf litter and debris that I haven’t yet cleared so early in the season. It’s the embodiment of the hope of spring and renewal, with its delicate, bird-like markings of indigo and soft yellow. A hybrid of two reticulated Iris with unpronounceable Latin names that I won’t bore you with, it’s also a very vigorous and reliable cultivar that increases for us year by year and is readily available from most mail-order bulb houses. There are other good Iris reticulata cultivars to try as well, in vivid shades of blue, violet, and magenta, but Katherine calls for a setting of her own, away from her gaudier cousins. Most of my garden’s successful combinations have been accidents, but I’ll give myself credit for this one because it was intentional. I grew these plants separately for years before realizing that their bloom time overlapped perfectly and their contrasts of color and form worked well together. The hybrid Trout Lily ‘Pagoda’ is as tough as it is charming, returning reliably every year from its strange, fang-like tubers with clumps of fresh and juicy foliage that’s attractively mottled. Following soon after are multiple scapes of nodding, lily-form flowers in softest primrose yellow. The dark Hellebores are mostly ‘Blue Lady’, with some unnamed dark seedlings thrown in, and a clump of the fine double-flowered ‘Onyx Odyssey’. The increased popularity of Hellebores (they’ve become something of an “IT” plant) means the market is flooded with varieties from many hybridizing programs. I’ve tried lots of them, and in my experience those developed in the US do better in our harsh northeastern winters than some of the gorgeous cultivars that are coming out of England and Holland. ‘Onyx Odyssey’ is just a really good variety, bred in the Pacific northwest, and part of the Winter Jewels series that includes singles and doubles in many beautiful shades. I don’t plant many trees these days because our property is already shadier than I’d like… a grove of huge Silver Maples, most of them on the neighbor’s property to the south, hang over us and cast just enough shade to make it tricky finding a spot for sun-loving plants. But we wanted to plant something special in memory of our beloved German Shepherd, Max. I stumbled on this Magnolia hybrid, ‘Genie’, that I was unfamiliar with but sounded promising, and it’s turning out to be a fine choice. Of course, as with many of the spring-blooming Magnolias, you’re always playing a game with late frosts. Rather than see it spoiled, and because it’s still smallish, I went out of my way to wrap it for a couple of freezing nights in mid-April. It saved the buds and also had its own curious appeal, something like a Noguchi lamp outdoors! There are other Magnolias in this deep color range, but the thing about ‘Genie’ is that every part of the cup-shaped blossom is this lovely burgundy shade, even the inside of the petals (technically tepals). A little research reveals that this is a cross between Magnolia x soulangeana and Magnolia x liliflora, developed in New Zealand and said to mature at around 10 to 15 ft. Ours is already nearly that tall and shows no signs of stopping, so we’ll see how it develops. Whatever size it turns out to be, we love it and consider it a fitting tribute to our Max. A couple weeks after the Magnolia bloomed, the Tulips moved the show to another part of the garden, in this case our south-facing dry terraced beds. The area was originally an unmowable, unmanageable bank of weeds, so we cut it into terraces and built informal stone walls that step down from the house level to the lawn below. It proved to be the perfect spot for Sedums of all kinds, Lavenders, the smaller clumping Alliums, Pussytoes, Pasque Flowers, Verbascums, and some drought tolerant grasses… in fact, anything that likes a real summer baking is happy growing there. As are Tulips, I discovered, which originally came from places like Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey…climates with cold winters, cool wet springs, and hot dry summers. I started out planting a favorite species Tulip, Tulipa orphanidea subsp. whittalii, (left above, in bud) a charmer with the unusual color combination of burnt orange, yellow, olive green and black. Another winner is the multi-flowered Tulipa praestans cultivar ‘Shogun’ (right above). Although Tulips come in every shade of the rainbow, and many gorgeous blends, all tempting, I’ve been keeping the palette to orange, bronze and brownish varieties that complement the bright emerging foliage of the Sedum ‘Angelina’, with a dose of sky blue for contrast courtesy of a good Creeping Phlox cultivar, ‘Oakington Blue Eyes’. That’s Tulip ‘Brown Sugar’ above, with Tulipa orphanidea subsp. whittalli. But this fall I ordered and planted several varieties with deep magenta blooms, so we’ll see how that pans out. I plant all of them super deep, and that seems to encourage them to perennialize. Before the spring bulbs had finished flaming, the herbaceous plants were well underway in their seasonal growth, providing more subtle but no less beautiful points of interest. Lately I’ve been geeking out on the Sedges, as have many gardeners interested in more naturalistic plantings. These plants, members of the species Carex, are tremendously varied natives that provide a needed grassy texture to shady areas where most true grasses won’t thrive. One of my favorites is the Fringed Sedge, Carex crinita. Struck by its graceful pendant tassels of bloom on several clumps already existing on the property, I took my cue from them and planted about thirty more from landscape plugs. They’ve bulked up nicely in the three years since, and now hang over the path in our wet meadow planting, flowering along with the bright yellow sprays of one of the Golden Groundsels, Packera obovata. The Packera is the only bright flower in this area in late spring, but the fresh, emerging foliage of perennials and biennials is plenty satisfying, at least to my eye. Pushing up alongside the Packera and Carex are Angelica gigas, Iris ‘Gerald Darby’, Geranium wlassovianum, and Eutrochium maculatum ‘Gateway’. In a couple more weeks they had knit together to form a weed-resistant tapestry of foliage that flowered later in the season. This idea of a weed-resistant tapestry or mosaic of plants is one of the foundational principles of naturalistic gardening, a version of ground cover that uses a combination of several plants rather than a monoculture, what garden designer Claudia West means when she says, “the plants are the mulch”. I’ve been experimenting with this idea here in several areas, but especially in what I call the wet meadow, a corner of our property that was always too damp and shady for a satisfactory lawn. One combination I’m using is the photo above, with Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium dubium ‘Baby Joe’) rising through a matrix of Palm Sedge (Carex muskingumensis), Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum muticum), and Wild Ageratum (Conoclinium coelestinum). The Mountain Mint and the Wild Ageratum can be extremely vigorous on their own, so I’m anxious to see how they fight it out. So far, and this will be the third year for this planting, the weed suppression has been very effective and the textural contrasts satisfying. Adjacent is an even wetter area that I planted with Lurid Sedge (Carex lurida), Marsh Spurge (Euphorbia palustris), Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris), and Canada Anemone (Anemone canadensis), creating a matrix around and beneath native wetland shrubs like Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis) and Maple-leaf Viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium). The Lurid Sedge is a cool plant, thriving in very wet shade and providing a medium scale grassy texture all season, and these very cute caterpillar-like spikelets in early summer. It’s called Lurid Sedge because the foliage is a little more yellow-green than other sedges, particularly when it first emerges in spring. If you’ve heard one of my talks around the area, or taken my class at the Berkshire Botanical Garden (which we’ll be doing again this spring) you know that I’ve been working on this wet meadow project for the past three or four years as a learning and teaching exercise. My method has evolved to include larger one- and three-gallon plants interspersed among the small landscape plugs that make up the majority of the planting. These plugs were planted about a hand’s breadth apart, in late May. You can see how different this just-planted area looks from what the typical landscaper’s perennial planting would look like… large, lonely perennials dotted around with yards of mulch in between. Here the idea is to use the smaller, deep-rooted plugs to establish quickly and take off in growth so the ground is covered completely within the first couple of seasons. That late May installation was followed by the hideous drought we had for most of June and July, during which I met lots of my neighbors who were out walking while I was out watering. But I got the baby plants pulled through, and by the time the rain returned in early August they had rooted in well enough to take a huge spurt in growth, as you can see above. This planting is a somewhat drier, sunnier part of the wet meadow, so the idea was more of a flowery mix of grasses and perennials. About 75% natives (I’m not a purist), it includes Asters, Rudbeckias, Geraniums, Winecups, Rattlesnake Master, Salvias, Turtleheads, Joe-Pye Weeds, and several varieties of grasses and sedges. By late September I was delighted, and a little surprised, to see they had filled in so much, and many of the faster growers were already flowering quite nicely in just the first season. As you can see, there’s already very little open ground left for weeds to colonize. This corner of the planting features a combination of Asters ‘Little Carlow’ and ‘October Skies’, Rudbeckia subtomentosa ‘Henry Eilers’, Agastache nepetoides, Rattlesnake Master (Eryngium yuccifolium) and Korean Feather Reed Grass (Calamagrostis brachtyricha). In another part of the property is an area I call the Dark Border. It’s full of self-sowing Opium Poppies from late spring until the end of June, when they get pulled out and I plant it up with tropicals and annuals in a deep, rich color scheme. Always included in the mix are the Castor Bean ‘New Zealand Purple’, which I grow from seed, dark-leaved Cannas, and the enormous deep black-purple grass Pennisetum purpureum ‘Vertigo’. This tender grass is pricey to buy every year at a nursery, but worth the splurge as it has such height and presence, and none of the purple-foliaged perennial grasses are nearly as dark. There are several deeply colored perennials here as well, including Actaea simplex ‘Hillside Black Beauty’, Bronze Fennel, and Geranium phaeum ‘Samobor’. And a couple seasons back I discovered this beautiful cultivar of the native False Sunflower, Heliopsis helianthoides ‘Bleeding Hearts’. The foliage, buds, and stems are suffused with purple tones, and the daisy-form flowers open in shades of deep red, maturing through burnt orange and fading to golden yellow. All these various flame shades are displayed on the plant at the same time, an effect some may not like but I find delightful. Heliopsis can be a bit lax and willowy in their habit… some might even say floppy… but that quality isn’t a problem when they’re allowed to weave among strong growers like Cannas, Bronze Fennel, and Castor Beans. ‘Bleeding Hearts’ has a very long season of bloom, and pairs well with other jewel-toned flowers like Drumstick Allium, the strong ruby-red Daylily ‘Frankly Scarlet’, and later in the summer, Verbena bonariensis. As a bonus, the flowers seemed very attractive to bees, butterflies, and other pollinators. I especially like it near the multi-hued Canna cultivar ‘Phasion’. This year was only my third year to grow ‘Bleeding Hearts’, so I’m still considering it under evaluation. Some references list it as “short-lived”, but so far it’s returned reliably and remained in compact clumps, showing no invasive tendencies. Another plant I’m keeping a critical eye on is the Ghost Bramble. It’s a Raspberry relative that sports delicate silver foliage in summer, and dramatic white winter stem coloring. It makes a fine companion to late-season standouts like Salvia splendens and Lespedeza thunbergii ‘White Fountain’, above. And it provides interest well past frost, when the chalky white coating on the stems stands out against the browns and greys of late fall. I’ve unfortunately lost my original label and record of where I got this plant, about eight years ago now, and my googling only yields more confusion as to its identity. Seems there are several plants sold under the common name “Ghost Bramble”, including Rubus cockburnianus, Rubus lasiostylus, Rubus biflorus and Rubus thibetanus ‘Silver Fern’, which I think is probably the one I have. An experienced gardener I know has grown a version that was far too rambunctious, spreading far and wide by runners, but that hasn’t been the case with mine… it’s only made a couple of divisible offsets in the eight years I’ve had it. Whatever it’s identity, I like its graceful arching habit, its cool dainty foliage, and especially the waxy white coating that distinguished the bare canes. Like most shrubs grown for winter interest, the best coloration is on young stems, so Ghost Bramble gets cut to the ground annually during spring cleanup.

Out my window it’s bleak… a Bruegel landscape of white, black, grey and brown. Looking back at these photos, I can hardly believe there was so much lush, fresh, green vegetation, and so much color in flower and leaf. But it gives me hope for the promise of another new year, another chance at renewal and growth and gratification. Despite the brutal challenges of 2020, in the garden, at least, there was fulfillment, beauty, and profound peace of mind. May we all find the same in the coming year. My heartfelt thanks to everyone who subscribed to the Zoom talk today, and appreciation for your support of Spencertown Academy's "Hidden Gardens" annual event. We're all hoping by next year the tour and market will be back, and the lecture will again be held in person (with breakfast!) I'm posting this additional information here, in place of the handouts I would normally give a live audience, for those of you who want to delve deeper into the topic of naturalistic planting design and practice. First, a reading list (yes, I still read books). Naturalistic planting is a hot topic in the gardening world so as you can imagine there are lots of books being churned out right now, most of them so-so and some downright worthless. Here are a half-dozen I've found to be indispensable, and to which I return over and over again for inspiration and information. Essay on Gardening Henk Gerritsen This "essay" is almost four hundred pages long, but it's still the seminal work that outlines the philosophy and evolution of the Dutch Wave in planting design. Sounds intimidating but trust me it's a wonderfully easy read and a gorgeously designed book with many beautiful photographs. Sadly, Gerritsen died in 2008, but his writing continues to guide and inspire. Dream Plants for the Natural Garden Henk Gerritsen and Piet Oudolf My bible for perennial plant selection, not a thick reference but the distillation of decades of trial and error by Piet and Anja Oudolf at their nursery in the Netherlands. Gerritsen's text is succinct, opinionated and amusing, and the way the plants are classified by tough to difficult to ephemeral makes sense to any real gardener. Out of print but available on Alibris (better source of used books than Amazon). Planting in a Post-Wild World Thomas Rainer and Claudia West Still the best hands-on book for understanding how plants are layered in nature and how to translate that idea into a garden setting. Great diagrams and illustrations (one of which I pilfered for the lecture) really demonstrate how plants coexist at great density both above and below ground. Also defines several landscape archetypes that humans recognize and respond to emotionally. Beth Chatto's Gravel Garden Beth Chatto All her books are worth reading, but this is the one that I go back to again and again. It's a fascinating story of how she turned a gravel parking lot at her nursery into one of the most famous gardens in the world. The perfect illustration of how to work with the site conditions you have, and how to put into practice the maxim of "Right Plant, Right Place". The Encyclopedia of Grasses for Livable Landscapes Rick Darke This is the updated and improved edition of Darke's essential 1999 book, The Color Encyclopedia of Ornamental Grasses, now with over 1000 photographs and descriptions of grasses, sedges, rushes, restios, and cattails. The popularity of these plants continues to grow, and they are used extensively in naturalistic planting, so understanding their diverse needs and qualities is key to good design. The one book you need on grasses. Planting, A New Perspective Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury Essential reading for superfans of Oudolf, this is a detailed explanation of his philosophy and design process. Given the scale of most of the projects, and the budgets he commands, the information is of limited use to a home gardener, albeit fascinating. A better bet for most of us is to see the film "Five Seasons" which covers the same ground in a more entertaining way. Weeds of the Northeast Uva, Neal & DiTomaso I couldn't resist adding this because I never tire of recommending it to gardeners, even though it really is extreme horticultural geeking to read about weeds. But, this is a great reference that has excellent photos of our local weeds in all stages of development, highly useful when you're trying to decide whether that seedling is a poppy or a thistle. ************ In the Zoom talk I showed you how I plant using deep landscape plugs, and here are a few sources. Be warned that most have minimum annual purchases to establish an account, and as wholesalers, can be strict about selling to individual customers. However, most of them will sell to a garden club or a community garden organization if the minimums are met. North Creek Nurseries https://www.northcreeknurseries.com/ Hoffman Nursery http://hoffmannursery.com/ New Moon Nursery http://newmoonnursery.com/ Prairie Moon Nursery https://www.prairiemoon.com/ ************ Finally, here's a subjective list of what I think are key names in the history of this movement and some of the best current practitioners. Almost all the contemporary designers have websites and/or can be followed on social media, so you can easily see many of their projects developed and completed. Netherlands: Mien Ruys (designer, writer) Henk Gerritsen (designer, writer) Ton ter Linden (artist, designer) Piet Oudolf (designer) Tom de Witte (designer) Germany: Karl Foerster (nursery, writer) Cassian Schmidt (designer) France: Gilles Clement (designer, writer) Britain: William Robinson (writer) Gertrude Jekyll (designer, writer) Christopher Lloyd (designer, writer) Fergus Garrett (designer) Beth Chatto (nursery, writer) Noel Kingsbury (writer) Dan Pearson (designer) Sarah Price (designer) Tom Stuart-Smith (designer) Arne Maynard (designer) James Hitchmough (designer) Nigel Dunnett (designer) United States: Wolfgang Oehme & James van Sweden (designers) Roy Diblik (designer, writer) Thomas Rainer & Claudia West (writers, designers) James Golden (designer, writer) Christine Ten Eyck (designer) Rick Darke (writer, photographer) Thanks again, to all participants, and to the staff and board at Spencertown Academy for facilitating. Happy gardening to you all! R There are well-mannered plants (good) and invasives (bad)... and then there are those plants that are charming, beautiful, useful, even irreplaceable in your garden for many reasons. But they're rambunctious. They spread a bit much, they reseed with abandon, they just cause extra work and headaches. And yet, and yet... we can't quite banish them. As the weather warms, up come seedlings of many of these that reproduce as annuals, requiring not planting but editing... decisions must be made as to how many of the sometimes thousands of progeny are to remain. It's tempting to leave them alone and not sacrifice any, but not the best practice horticulturally, as overcrowding prevents strong plant development and flowering. But easier said than done, of course. Every year I have the best intentions of thinning the Opium Poppies, but there's so much else to be done during that time that I never quite get around to it... and inevitably the plants that have seeded in unlikely spots, alone and unmolested by their peers, have the most beautiful foliage, and the largest and loveliest flowers. Then there are the spreaders, mostly perennials, that are what the great plantsman Tony Avent calls, "not exactly invasive, just overly friendly." Curbing their enthusiasm is a regular annual task, but a little shovel pruning does the trick and provides plenty of pieces to be given away, potted up for donation to plant sales, or used in other parts of the garden. It's all a matter of taste and balance, but there's no doubt that some plants that cause us extra work and worry are just indispensable. Here, in no particular order, are a few that I can't garden without, despite their willful dispositions . . . Verbena bonariensisThis is one of the trendiest annuals of the last few years, and with good reason... super easy to grow, self-sowing, heat and drought tolerant, a good color, pollinator friendly, and nothing else looks quite like it. A native of South America, but there are similar though less showy species here in the US, so it looks reasonably at home here and not obviously exotic. I find it very useful in informal plantings where it complements grasses and grows tall enough to stand above all but the largest ones. Seeds itself generously but I always seem to be able to use the extras somewhere, easily transplanted as they are. Pinching the top of young seedlings or those wilting from a move will yield a nicely bushy, more floriferous plant. The one drawback I can think of is that the seedlings really look like weeds, so edit with care until you learn to recognize them. Forget-Me-NotsHard to imagine that anyone could consider Myosotis sylvatica invasive, but I've heard some gardeners say so, and indeed it's listed as a Noxious Weed by some midwestern states. Hummmph. I like that it travels all over the garden and don't find it hard to pull up or hoe out where it's not welcome. Pools of sky blue for almost a month starting in mid-May, dainty and gauzy filling around taller plants like the Japanese Woodland Peony above. Its biggest drawback, in my opinion, is the less-than-lovely phase it must go through after flowering in order to ripen its seeds. But I find that even if I remove 90% of the plants at that point, there will still be plenty of reseeding to continue the colonies. It won't stay put, however, so don't count on it being in exactly the same spot every year. Needs moist soil and will tolerate full sun but lasts longer with a little shade. Also great around and among Hostas, whose expanding leaves will help mask the post-bloom seediness. Anemone canadensis This innocent looking wildflower would appear on many gardeners' invasives lists, because like most Anemones it spreads by underground runners and is a tough American native. I've seen it run amok in a flower bed, so don't plant it there. But at our place it isn't uncontrollable, maybe because I use it in the shade underneath shrubs and large grasses where little else will grow. It spreads vigorously and suppresses most small weeds, and provides its fresh and charming single white flowers for a couple of weeks in late May, followed by fine-textured foliage that looks nice until frost. Almost impossible to find in a nursery, but anyone who has it will probably be happy to give you a bucketful. Opium PoppiesAlso known as Bread Seed Poppy or Lettuce Poppy, Papaver somniferum has been cultivated for millennia, valued as a garden ornamental but also as a food plant (the seeds) and as a pharmaceutical (the latex sap). Only certain strains produce enough latex to harvest, but all of them produce prodigious amounts of seed, so three or four pods left to ripen will ensure hundreds of seedlings the next year. These need to be thinned to allow the plants, which become quite large and leafy, to develop properly... a task I can never seem to manage. Nevertheless there are always plenty of blooms, and for the past several years I've been selecting the colors I like best, marking those plants, and allowing them to ripen their pods fully. All the others get pulled out ruthlessly after they flower and replaced with heat-loving annuals and tropicals that occupy the space until frost. The default color seems to be an attractive lavender-pink, sometimes with fringed petals, but I'm selecting for the jewel tones... deep violet, true red, intense coral. A good color to start with is 'Lauren's Grape', available from Select Seeds https://www.selectseeds.com/Search/papaversomniferum.aspx which also sells several other nice colors, including a pure white. The seeds need cool soil and a bare patch of ground to come up but once you have them going they'll pop up everywhere, as they do here... in the paths, the cracks in pavement, even out in the chicken yard (not sure how they got there). Having a taproot, they're difficult to transplant, but easy to remove where they're not wanted. The individual flowers only last two or three days but there are usually multiple buds on each plant, and the pods that are allowed to develop are decorative in their own right, and fascinating in their complex structure. ValerianValeriana officinalis is called Garden Heliotrope, and it does indeed share that plant's warm vanilla-ish fragrance. Often included in herb gardens because of its use in treating anxiety and insomnia, it can become a problematic spreader if planted in rich, moist soil, but I find it fairly easy to control by deadheading and removal of some outer rhizomes annually. I love its old-fashioned look, and when it runs up to bloom, nothing else is quite so vertical. The ferny foliage remains handsome and a glossy dark green after the pinkish white flowering in early June. NicotianasI've had a running love-hate affair with Nicotianas, the Flowering Tobaccos. For the past four or five years I've been on a complete eradication binge, annoyed by their massive self-sowing and frustrated by their tendency to cross-breed away from the desired color or form. So they've been going down to the hoe for a few seasons, but just as I've finally managed to eliminate them, I'm feeling charmed again. So I think I'm ready to sneak back in just one... and it's going to be Nicotiana mutabilis, with airy panicles of bloom that hang like little trumpets, changing from white to pale pink to deep pink as they age, all displayed at the same time. Nicotianas are easy to grow, long-blooming and never need to be purchased more than once. Besides mutabilis, other good types are Nicotiana alata (white flowered and very fragrant), Nicotiana sylvestris (tall, with pendant white flowers), Nicotiana langsdorffii (lime green flowers with cobalt blue pollen), and many smaller bedding types in a wide range of colors. CampanulasBeautiful but dangerous, Bellflowers can range from vigorous colonizers to rapacious spreaders. I'll never again make the mistake of planting Ladybells (Campanula rapunculoides) unless it's in a parking lot, and maybe not even there. Her demure spikes of pendant lavender bells belie a ravenous appetite for spreading and her parsnip-like root penetrates the ground a foot or more. Ladylike she is not. Much more manageable are some of the species from China and Korea that mingle in my woodland underplantings without causing so much disruption. I've had Campanula punctata 'Alba' (above) for many years now and I still look forward to its flowering every summer in shady moist ground, where the sprays top out at about a foot tall. In Asia these aren't called Bellflowers but Lantern Flowers, which makes sense too. A newer species I've had for only a couple of years, but I'm liking very much, is the smaller Campanula kinokawamae, with palest pink bells on 8" stems. It wanders in and among small Sedges, Packera, and Golden Filipendula, covering ground and suppressing weeds in a damp area under Hawthorn trees. If you'd like to try it, it's available from one of my favorite quirky, locally owned mail-order sources, Quackin' Grass Nursery in Connecticut... https://www.quackingrassnursery.com/ Bronze FennelOne of my very favorite plants... texture, color, structure, flower form... everything about this beauty makes me swoon. So I don't mind its faults, which are that it often needs staking, and always drops a million seeds. Tufts of brownish-purplish-green emerge in spring and become clouds of feathery foliage by early summer, then onward and upward to the flowering umbels of light greenish yellow, alive with pollinators and the caterpillars of the Black Swallowtail, for which it is a major food. You can eat it too, if you can bear to remove it from the flower border, where it complements nearly everything. All Fennel is beautiful and delicious, but the Bronze version, Foeniculum vulgare 'Purpureum' is the one I grow. You can deadhead in late summer to reduce the seeding, but whatever sprouts unwanted in spring is easily dispatched with a hoe or cultivator. VioletsSweet and old-fashioned, Common Violets won't impress a plant snob but I think they're very useful to fill in around larger perennials in naturalistic plantings. As you may have noticed, they're one of the earliest perennials to be visited by bees and other pollinators. Also, they're free, coming up all over most everyone's lawn. Ours were all deep purple but a friendly gardener shared some white ones with dark centers, so now they mingle together. They reproduce by seeding as well as by runners so they can cover a lot of ground in no time... ground that would otherwise be colonized by weeds. And since they're free and plentiful I never feel guilty about pulling them up where I don't want them any longer. Amsonia hubrichtiiSome people say they have a hard time getting this plant established, but it's practically a nuisance with me, liking my soil enough to reseed madly around the mature plants. I don't mind because there's always someone who wants a few, once they see the sky-blue flowers in June or the yellow foliage in the fall. Plus if you let some of the seedlings develop you'll get interesting color variations... I now have a pure white and a smokey grey flowered version in addition to the clear blues of the original plants. The seedlings have a taproot but are so drough resistant that they transplant easily and recover quickly. I love their willowy form and feathery texture after flowering, but I understand they can be sheared back if a more compact shape is wanted. Native to the Ouachita Mountains in Arkansas but perfectly hardy here. PerillaPerilla frutescens is the Shiso, a plant used extensively in Japanese and other Asian cuisines, and in traditional Chinese medicine. There are both green-leafed and red-leafed forms, as well as a variegated version sold as 'Magilla'. Also called Chinese Basil or Beefsteak Plant, it's a mint family relative but grows from seed and has a fibrous, not a running, root system. And seed it does, by the hundred (maybe thousand!). But I use it as a filler plant, so I like to have lots, and the unwanted seedlings are easy to see from a very young age and easy to remove. Just think of it as a free Coleus! Like Coleus, it benefits from being cut to half its height around the 4th of July so it stays nice and bushy for the rest of the growing season. Garlic ChivesMany members of the Allium tribe are very accomplished self-sowers, so you've got to keep an eye on them and deadhead the most prolific. Which is hard to do because they often have decorative seed heads that it's tempting to leave in place through the winter. With most Alliums, I do leave them up, but I learned my lesson with Garlic Chives, Allium tuberosum, and now religiously decapitate it soon after bloom. It still spreads reliably via offsets so I'm thinking it might be a good candidate to plug into a meadow style planting... if fact I know a spot on my regular route where it grows on a ditch bank beside a busy highway. We keep a patch in our herb bed, close to the back door, for use in lots of dishes (omelettes, in particular) but it's the clean, cool white heads of bloom that I appreciate the most, coming as they do at the hottest time of the summer. VerbascumsCommonly called Mulleins, most Verbascums are prodigious self-sowers, as evidenced by the roadside colonies one sees, and the garden varieties are no less fecund. I spite of the thinning that must be done every spring, I wouldn't want to be without them, because few plants offer the same comportment... bold rosettes of large leaves, often furry or silvery, above which are carried tall spikes of bloom, each flower small but in mass quite effective. There are many good kinds that must be grown from seed or received from another gardener; rarely are they available in nurseries. I've had lots of them over the years, but my favorite right now is Verbascum chaixii 'Album', a white flowered form of the Nettle Leaved Mullein, which is typically yellow. It thrives in my sunny dry terrace beds, blooms for more than a month, and the white flowers with purplish centers seem to go with everything. To my eyes, Verbascums look equally at home in a cottagey mashup or in a formal perennial border, which you can't say about every plant. Euphorbia myrsinitesDonkey-Tail Spurge is one of those "cute" plants that always catches the eye of children and novice gardeners, in other words people who aren't jaded plant snobs (yet). It's also one of those plants that's tricky to get started, but once going it will be with you for the long haul. Like all Euphorbias, its acid yellow flowers are a visual tonic early in the season, and they complement the coarse silver foliage, which looks sharp but is actually more rubbery to the touch. It loves to grow in scrabbly, dry and gravelly areas, so use it there instead of a rich garden bed, where it tends to rot. It also won't stay put but insists on traveling around and planting itself where it wants to be. Cute, but capricious. Bearded IrisI include these in my list not because they spread problematically but because they need division every few years, and they're so beautiful when they bloom that it's hard to just throw away the extra rhizomes. This old farmstead variety is Iris pallida, the Dalmatian Iris, and I love it because it flowers so reliably and fragrantly around Memorial Day, and the silvery leaves stay mostly undiseased for the rest of the season (unlike many of the modern hybrids). Bearded Iris like to bake in a dry spot during the summer, and there are hundreds of named varieties from which to choose. If you want to see some really ravishing cultivars, check out the Benton Irises, developed by Sir Cedric Morris, a famous British artist and plantsman. https://www.gapphotos.com/featuredetails.asp?view=sir-cedric-morris-irises-national-collection-&featureref=3029

Whether they spread by offsets, runners, rhizomes or seeds, these are plants I can depend upon to never be without... even if they move around a bit each season, or ebb and flow in numbers from year to year. This unpredictability might annoy tidier gardeners, but it fits my current garden aesthetic, which seems to become freer, looser and less controlled as I age. Undoubtedly as it should. This is a very personal list, reflecting not only my preferences and prejudices, but also what thrives... sometimes a bit too well... in my garden's particular conditions. Your list of troublesome but beloved plants is surely different, and will reflect your tastes and your garden's ecology. But we can all agree that some plants, like some people, charm us enough that we overlook, tolerate, and even celebrate their flaws. It's worthwhile to keep on cultivating both. Obviously, I love plants and gardens, but I must admit that I've been less than enthusiastic about the current revival of interest in indoor plants. For many of us who live through the 70's, the idea of "houseplants" revives less-than-fond memories of dusty Scheffleras, defoliated Ficus Trees, and mangy Spider Plants in rotting macramé hangers. But a major trend it is, as demonstrated by the sustained interest of many thousands of enthusiastic (mostly young) people... and the remarkable popularity of many online sources of inspiration and obsession. The wave began several years ago as a ripple of interest in succulents, noted by those of us who were working in retail plant sales. Succulents are the perfect horticultural gateway drug... visually appealing, endlessly varied, and most importantly culturally forgiving... success with them is not guaranteed but highly likely, and many youngsters got hooked. The ready availability of reasonably priced tissue-cultured Orchids in recent years sparked an interest in that group, and from there it's an easy jump to all sorts of tropical foliage plants that can be grown indoors. A quick online search will yield hours of video how-to's on identification and culture of everything from current "It" plants like Fiddle Leaf Ficus and Pencil Cactus to more obscure and specialized groups like Hoyas, Lithops, and Rex Begonias. If you think I'm exaggerating, check out some of the related social media, like this Instagram account @boyswithplants ... it's just for fun (thanks, Betty Grindrod, for the suggestion!) but there are some very good YouTube channels for real in-depth information, like Plant One On Me, with dozens of videos hosted by Cornell graduate and eco-model Summer Rayne Oakes. Another popular YouTube channel is Planterina, with almost 300,000 subscribers and more than 100 videos related to houseplant identification, care, and propagation. And if you really want to go down the rabbit hole, there are hundreds of videos of regular folks just giving a video tour of every houseplant they own. It's plant geekery at its best, and I love it. Having lived in cramped city apartments for years, I can certainly relate to the hunger for life and greenery that houseplants satisfy, but now that I have two outdoor acres to play in, I no longer feel the need. I do overwinter some Begonias and succulents that decorate our porch and entrance stoop in the warm months, but they're temporary indoor residents. In spite of my lack of enthusiasm for houseplants in general, I always enjoy seeing plants used in unexpected ways, as we did on a trip to SE Asia over the holidays. In any tropical locale it's startling to see plants we know as indoor specimens growing outdoors, some of them as locally native species. Look carefully in the lower right corner of this photo and you'll see a fine specimen of Pencil Cactus, Euphorbia tirucalli, growing out of a cliff overlooking the Indian Ocean. This very popular houseplant is originally native to Africa but can now be found growing as a weed all over the tropics. This bears little resemblance to the haggard, leaf-dropping specimen that graced my college apartment, but it's a Ficus Tree as it grows in nature. Ficus benjamina, the Weeping Fig, is still a popular indoor plant and quite attractive when well grown, but it can never match the magnificence of a mature tree in the tropics. I thought these carved stone identifiers at this nature park in Bali were particularly nice. Weeping Fig (or Beringin as it's known in Indonesia) is native to SE Asia, bearing small fruit that's an important food source for several species of tropical doves. Here's a patch of Monstera deliciosa that would make any Brooklyn homesteader weep with envy... this tropical vine, with its handsome fenestrated foliage, is often seen growing up the trunks of tall trees. Called Swiss Cheese Plant because of the characteristic holes that develop in the leaves, it also exists in a variegated form that's particularly prized here as a houseplant. The Madagascar Dragon Tree, Dracaena marginata, makes an excellent indoor plant as it tolerates dry air very well, and its upright, often multi-stemmed form is pleasing and easily accommodated in a room. This is the variegated form 'Tricolor', at home as an in-ground shrub in a temple courtyard. Aglaeonemas of many species are native all over SE Asia, growing in the filtered light of forest floors. That makes them particularly valuable as houseplants because they can tolerate the low light levels in many indoor situations. Here in the west they are known as Chinese Evergreen and have been hybridized into many forms with silver, spotted, and colored variegation. Another plant that tolerates similar low-light conditions is the Dieffenbachia or Dumb Cane (so called because the sap will cause paralysis of the tongue... who tried that???) It's a native of Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean, but has made itself at home in many parts of the tropical world. Large and showy leaves, easily grown indoors, and comes in many named varieties. Oyster plant or Moses-in-the-Boat is grown as a houseplant here, often in its variegated form, but in the tropics it makes a tough and reliable groundcover. The common names refer to the fact that the cooked roots supposedly taste like oysters, and the tiny white flowers (the Moses) are borne cradled within the rosette of leaves. At any rate, they need a decent amount of light to thrive indoors but are otherwise easy subjects. Native to tropical Mexico and Guatemala, their official name is now Tradescantia spathacea although often sold under the former name of Rhoeo spathacea. Possibly the most colorful foliage houseplant you can grow is the Croton, Codiaeum variegatum, which exists in a staggering variety of leaf shapes and colors. They do have a reputation for being somewhat finicky, dropping their leaves if too wet, too dry, too cool, or just from being moved. Once you find a happy spot for them they will recover, regrow their leaves, and settle in to become reliable and very decorative houseplants. Crotons are native to India and Malaysia, but grown worldwide. We saw many gorgeous examples in Bali, especially in the temple gardens. Philodendron bipinnatifidum is a large, handsome member of the huge tribe of Philodendrons, many of which make excellent and dramatic houseplants. It's native to South America but used as a landscape plant all over the tropics, and in Florida and the Gulf Coast states, where it can recover from the occasional light freeze. Green walls are a big trend now, and here's one that planted itself... at least three or four kinds of tropical ferns and a vine I can't identify, all growing happily together without any artificial maintenance, thank you very much. The Chicken Gizzard, Bloodleaf, or Beefsteak Plant, Iresine herbstii, is frequently sold here as a summer bedder and container plant but can also be grown indoors. It comes in many color forms and hails originally from Brazil, where it grows to shrub size. Cordylines are another plant often used in summer planters and mixed containers here in our area but they're actually shrubs that can reach 8-10 feet tall in frost-free climates. Native to eastern Australia, New Zealand, SE Asia and Polynesia, these handsome plants can be found in many color variations. To thrive indoors they require a bright light situation. We pay a pretty penny for Elephant Ears here, both Colocasia and Alocasia varieties, so it's amusing to see them all over Bali growing in irrigation ditches. Another familiar houseplant in the Cornstalk Dracaena, Dracaena fragrans. It's a native of Africa, where it's used as a hedge, but thriving here in a Singapore nature preserve. Slow growing, it can eventually reach a height of 50 feet in the tropics. The variety 'Massangeana' has a broad lime-green stripe down the middle of the leaf, making it a popular choice for indoor use. A medley of tropical foliage plants, here in a public park, is soothing to the eye and just about as satisfying as a flower border, in my opinion. Parlor palms, anyone? Whether you grow plants indoors or not, I hope you've enjoyed this little tour. Seeing familiar plants growing in unfamiliar ways is always a revelation. And if you're a newly minted houseplant loving, apartment dwelling, greenery obsessed millennial, god bless and please keep going! Olds like me may look on the current trend with a little amusement, but it's truly wonderful to see young people embrace what I hope will grow into a lifelong passion. Whether it will lead to an interest in outdoor gardening is yet to be revealed, especially in light of the fact that sadly, many in your age group find home ownership out of reach for now. But I hope it's the spark of a new generation of enthusiasts who can carry on as horticultural hobbyists and professionals... the gardening world needs you, and welcomes you. What plant nerd could possibly resist walking into this tropical nursery wonderland?

It’s been a slow and stately progression through the season here in the Hudson Valley; the weather and the leaves have changed gradually but surely, and we finally had a real killing frost here just last week. Always a beautiful time around here, and many people claim it as their favorite season, despite the danger of being run down by busloads of eager leaf-peepers on the back roads of New York and New England. The trees are so spectacular that no one really grouses about the lack of flowers in the garden, although there are a few hangers-on… Asters, Chrysanthemums and Aconitums are three that come to mind. But it’s not about flowers just now. The perennial garden is taking its turn towards being a study in texture and monochrome… the gradual annual transition from a painting to an etching. Still, there’s abundant color among herbaceous plants that we can note for future exploitation… why not plant for appeal at this time of year, as well as for the peak bloom periods? We’re often advised to choose trees and shrubs for more than one season of interest, so why not perennials too? If, for example, out of twenty similar pink Astilbe cultivars on the market, one of them has outstanding fall color, why would I not choose that one? Case in point is this Astilbe cultivar, ‘Delft Lace’, which bears delicate, somewhat open sprays of warm pink flowers in June and clean, deep green foliage all summer in the ferny texture that Astilbes are known for. If that’s not enough, it’s deer-proof and fairly weed suppressing once established. Then for an added bonus, when temperatures cool it takes on mottled shades of pink, red, gold and coral, varying somewhat every year. Now that’s a perennial that pays its way. Another Astilbe for multi-season interest is this dark foliaged variety, ‘Chocolate Shogun’… it holds the deep maroon color all season and the flowers are a pleasing creamy blush that blends well with everything, then age to these beautiful bronze seed heads. Most years it turns glowing shades of red in autumn. One note of caution: I have several plants from three different sources and they aren’t all the same. They all have the deep purple foliage but those that bloom with creamy flowers (not a definite pink) are the only ones that bear the bronze seed heads. The true, or hardy Geraniums are a vast tribe that includes many types that color up nicely in fall. This is the unpronounceable Geranium wlassovianum, the Siberian Cranesbill, a workhorse for damp soil in sun or semi-shade. Siberian Cranesbill blooms pinkish lilac on trailing stems that grow rapidly from a central crown to weave among other perennials in an attractive way, and as its origin suggests, it’s absolutely bone hardy. Another Geranium workhorse that has reliable fall color is the unbeatable groundcover Geranium macrorrhizum, the Bigroot Geranium. There are several forms with flower color ranging from white to magenta… this is ‘Ingwersen’s Variety’, an oldie but goodie with flowers of a nice strong bubblegum pink. Still flowering here as late as last week is the almost ever-blooming Geranium hybrid ‘Rozanne’, shown here weaving herself among the foamy pink inflorences of the Purple Love Grass, Eragrostis spectabilis. It’s a native grass that’s common on roadsides around here, and it’s being incorporated into plantings more and more often. Not much to look at in the foliage department, but the clouds of pinkish purple bloom are stunning when they have the right setting. Another small scale grass that ends the season with style is the Japanese Forest Grass, Hakonechloa macra. All its varieties are graceful and elegant throughout the year, but some of them have particularly nice fall color, like ‘Nicolas’, shown above. The lime green variety, Hakonechloa macra ‘All Gold’, is the fastest growing cultivar (that’s relative) and bleaches to a pleasing shade as the season winds down, while still retaining its pendant, willowy form. At the other end of the scale are some very large, sculptural grasses that color up well. Molinia caerulea, the Purple Moor Grass, has an upright vase-shaped form that lends itself to being used as an eyecatching feature in mixed perennial plantings. There are several good cultivars on the market, and I particularly like ‘Skyracer’ for its height and see-through habit. Add to that a lovely greeny-gold autumn hue and you have a real winner. Even larger is the Giant Sacaton, Sporobolus wrightii ‘Windbreaker’. This selection of the southwestern states native is hardy here in Zone 5 and makes a graceful mound of foliage topped in late summer by 6-8 foot plumes that age to tawny gold. One of the best pairings for larger grasses is with the Arkansas Blue Star, Amsonia hubrichtii. It’s a terrific plant, native to the Oachita Mountains of Arkansas but perfectly reliable here in the northeast, providing one of the best displays of fall color by any perennial. As frost approaches, the finely textured foliage takes on shades of lime green, coral and violet. Then it becomes a dramatic mass of bright golden yellow that’s unequalled among herbaceous plants. The fall color is enough to warrant growing it, but it’s equally fascinating in May, as the curious clusters of sky blue flowers unfurl like some undersea creatures. Stems and stalks can provide fall color just as well as leaves, as in these pinkish purplish branches of the Marsh Spurge, Euphorbia palustris. It’s another plant I like to use alongside large grasses to provide a foliar contrast in average to moist soils. I love its refreshing blast of acid yellow flowers in late spring, an antidote to all the pink and lilac that’s everywhere that time of year. In summer, the Marsh Spurge features interestingly textural seed heads and mounds of clean, medium green, deer-proof foliage that makes unobtrusive filler as other plants take the spotlight. And making the case that it’s a four-season performer, the desiccated winter stems curl inward to form an intricate, wiry sculptural sphere. Another Euphorbia that’s colorful all year is the much smaller Euphorbia polychroma ‘Bonfire’. A bit tricky to establish, and often not a permanent resident, but if you can succeed with it you’ll be rewarded by season-long shades of burgundy and ruby red, and as the frost comes, subtle overtones of lavender and violet. Epimediums are one of my favorite groups of perennials. I love them for their dainty early spring flowers and their beautiful foliage that smothers most all weeds. Not all of them color well in the fall, but I’m gradually learning which ones do… like ‘Purple Prince’ (above), which mutates through shades of caramel and peach as autumn progresses. Two more good choices are Epimedium rubrum (left), sporting fresh pink flowers in spring, and the hybrid ‘Freckles’ (right) with dappled leaves that turn a solid bright orange. Lavender and purple aren’t colors I usually associate with fall, but this Agastache ‘Blue Fortune’ was, I thought, quite decorative after being touched by a couple of light frosts. More lavender and silvery grey shadings in these seedheads of Liatris ‘Floristan White’, the beautiful Korean Feather Reed Grass (Calamagrostis brachytricha) and the towering domes of Eutrochium dubium ‘Baby Joe’, a trio that thrives in full sun and damp to wet soil. Don’t forget that green is a color too, and like pines and hemlocks growing among flaming oaks and maples, the deep green of Hellebores provides a satisfying counterpoint to the brighter colors of surrounding perennials and grasses. Sometimes the lowliest plants can offer a real color blast as temperatures turn chilly. This Sedum rupestre ‘Angelina’ sports chartreuse foliage all summer that flames into shades of gold and orange in the fall. So why lament the lack of flowers in October and November when there’s so much color and texture to hold our attention?… not only from our spectacular tree foliage but from ordinary garden perennials, if we only care to observe. Above, clockwise from upper left, Cinnamon Fern, Coreopsis tripteris, Persicaria ‘Firetail’ and Gillenia trifoliata all make a contribution to the fall garden.